A Little Bit of Zine All of the Time

This zine asks the reader to take a macro dose of “Modern Medicine” and head into the power driven narrative of the internet (as inspired by Jonathan Harris’s article by the same name). The zine reflects on how our collective behavior has shifted when users feel safe and untouchable behind their platforms of choice. The zine suggest that users can demand companies create positive behavioral change, and software engineers can demonstrate their influence to yield positive change.

Other articles and videos referenced include George Aye’s talk at SXSW 2018, “The Designers Weakness” and “Toward a conversation on digital resistance” by Black Quantum Futurism.

God’s Not Dead, He Lives On My Twitter

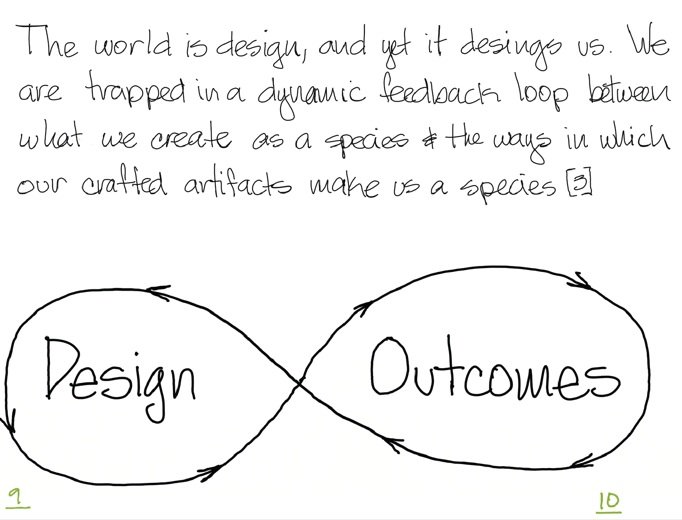

“God’s Not Dead, He Lives On My Twitter” — an interesting title you might be thinking. I see the power of design as almost like “playing God” because the impact of design decisions affects not only the world we live in, but who we are as humans. In this day in age of technology, social media has not only greatly shaped how we interact with each other and the world, but also how we perceive ourselves and our values.

Growing up with Instagram in the 6th grade was weird. Growing up with social media was weird in general because I would be such a different person without it. Sometimes I wonder if I’d be more confident or maybe just care less about what others think of me. Who knows. I’ve been designed I guess.

This is why “God” lives on my Twitter (there is a Twitter account @God, I recommend).

Zine heavily inspired by: Viral Zine

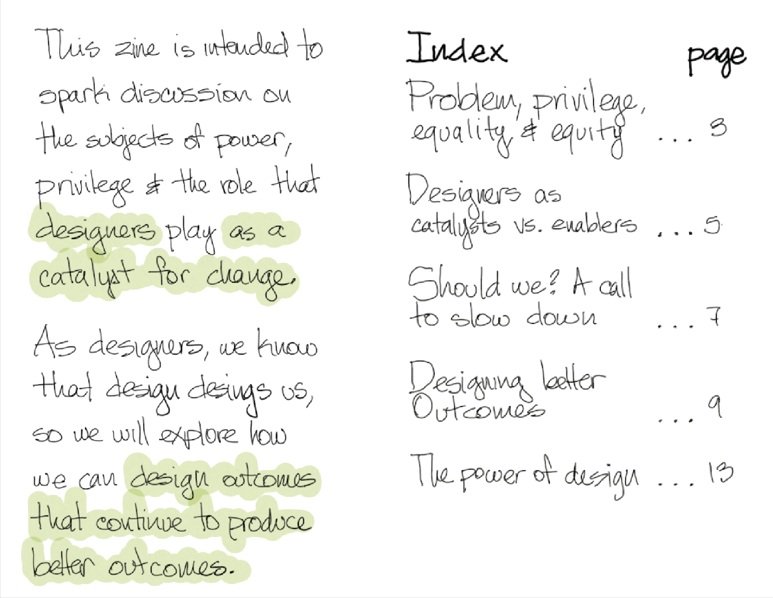

The World Designs Us and We Design It In Return

Ontological Design really speaks to me. Jason Silva has a good verbal introduction. If you prefer to read, check out Daniel Fraga.

Design is a feedback loop. We are intimately influenced by it. Through it, we have the power to influence our future selves.

Read Top Line First, from Left to Right

Read Top Line First, from Left to Right

Power <> Responsibility

Something that’s been top-of-mind for me lately is the potential for us, as future designers, to create things that may eventually impact hundreds, if not thousands (if not millions) of people, depending on the work we do and the projects we take on. That’s a pretty overwhelming thought! It weighs on me a bit.

We typically associate power with politicians, celebrities, executives, and billionaires – those who have clout, money, and quite a bit of sway – and the word tends to conjure up negative connotations, often being associated with greed and corruption. But what kinds of scenarios or situations might power be used for “good”? (“Good” in quotes because I mostly try to avoid using the good/bad dichotomy – life is more complicated than that.)

Yes, some people have a great deal of power, more than most of us. But having power simply means that one has the ability to effect change. That means policymakers, doctors, lawyers, and engineers hold power. That also means that educators, designers, social workers, therapists, filmmakers, activists, journalists, and citizens have the power to influence change of some sort. It might not be the same type of power, nor the same amount, but it’s power nonetheless.

As we’ve been digesting the words and work of designers and technologists such as Leyla Acaroglu, Curt Arledge, Jonathan Harris, Mike Monteiro, George Aye, and Ada A., it makes me wonder how many other folks in the tech and design community consider the power inherent in the decisions that they make – the ability to influence behaviors, experiences, and habits. And the ripple effect of those decisions.

I’m sure you’ve heard and/or read the quote, “with great power comes great responsibility”. Power and responsibility go hand-in-hand.

So what would our world look and be like if we in the design community took that responsibility as a deep commitment to invest more time, energy, and attention into building the “generative-hopeful-uplifting-energizing-bold-collective” type of power, to balance out the “greedy-corrupt-deceitful-unjust-extractive-exploitative” type that runs on the fuel we call fear, feeds on a mindset of scarcity, and consistently sabotages our shared culture, society, and humanity?

I pose this question not in despair or frustration, but rather to challenge the status quo behavior that seems to have overshadowed more creative ways of thinking and being, as we’ve pursued and prioritized “economic growth at all costs” (and there are, and have been many, costs), leaving marginalized groups behind and out of the conversation of what constitutes “growth” – not to mention, whether “growth” as we’ve seen it play out through conventional economic policy is even a responsible way forward and worth pursuing at this point, given what we know about climate change.

I also pose the question to call out the type of opportunity we all have to influence the culture we want to build, and to shape the society we want to exist and thrive in. All of us have the ability to shape culture – each of us has the power, no matter how seemingly small, to shape the culture of a group, space, community, team, etc. So I want to ask other up-and-coming designers the same questions I ask myself: what spaces do we want to step into and engage in, and how do we want to show up in those spaces? In other words, what do we want to care about – what do we want to invest our time, energy, and attention into, and to what do we want to lend our presence, actions, and focus?

The legacy we leave is based on the decisions that we make, and as designers, those decisions have the potential to impact people’s lives in ways we may not always clearly foresee, given our inherent biases. So what might it look like to start practicing more intention and care in the ways we approach design, especially in community with our stakeholders, and especially with those who are most affected by the things we design? In what ways can we exercise that power responsibly, particularly within the context of modern technology?

I admit, these are big, open questions that warrant further discussion. In the meantime, though, I made another bite-sized zine (read: we were asked to make a zine) to capture some sporadic and somewhat incomplete thoughts of mine, inspired by recent readings from our Public Sector, Innovation, and Impact class – check it out:

Technology, Design, & Social Responsibility

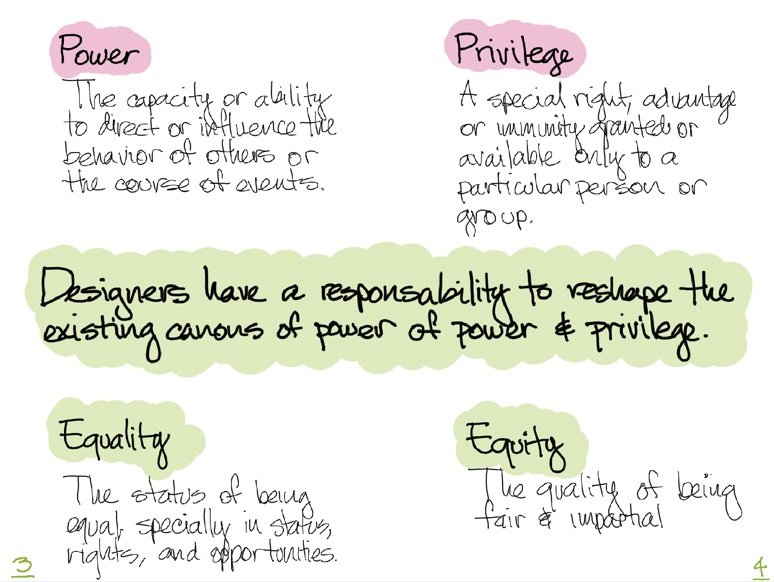

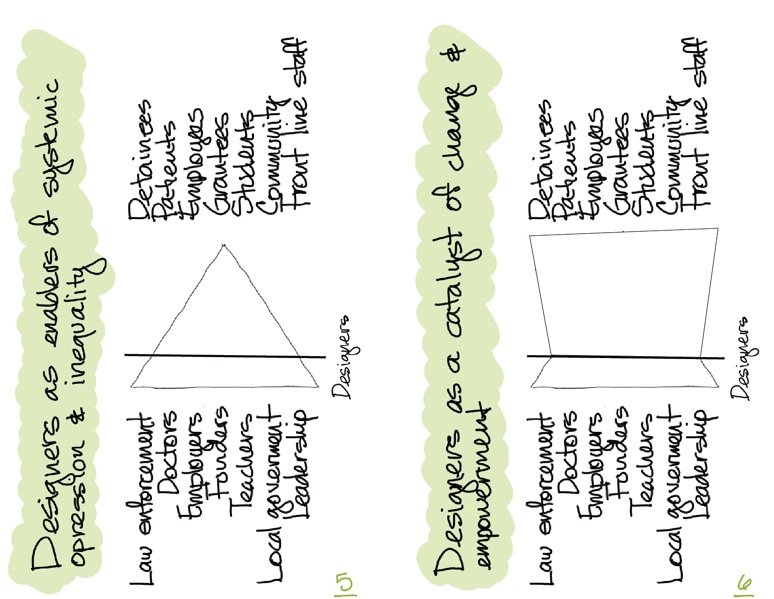

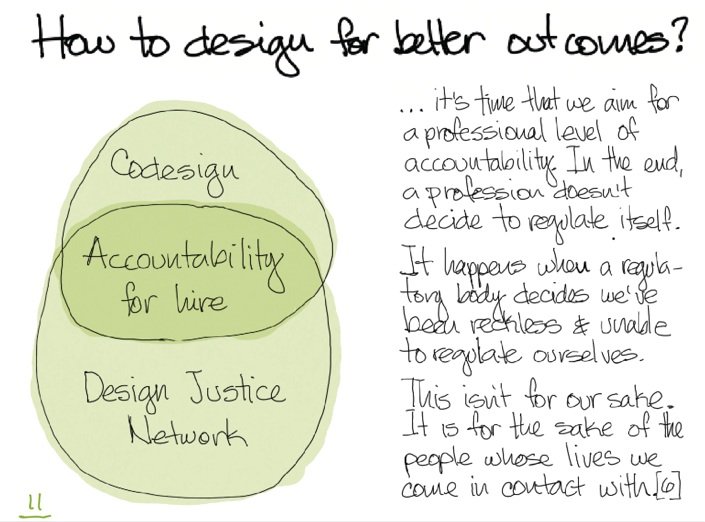

Over the past few weeks, in Theory class, we have discussed the topic of technology, design, privilege, and power. Designers have more power than they generally claim. It is time for designers to take responsibility for their power and use it as a catalyst to elevate people/users and communities.

In the context of technology, the conversation is always about “How fast can we deliver this new feature. What will the return on investment?” Of course, those are great questions that need answers. However, revenue questions should not replace questions about “What will be the implication of this solution? or How benefits from this solution and who is marginalized?”

The industry is missing accountability. It has grown fast and wide. Designers are no longer on a corner, working on the next cool gadget or magazine cover. Today designers are in the public sector, technology, health. Poor solutions lead to poor outcomes, especially for the people/users and marginalized communities during the design/solution process.

I do not have any answers, but I hope that we can continue having this conversation with this zine. And one day, with our design powers combined, we can create accountability that leads to better outcomes for the people/users and communities we serve.

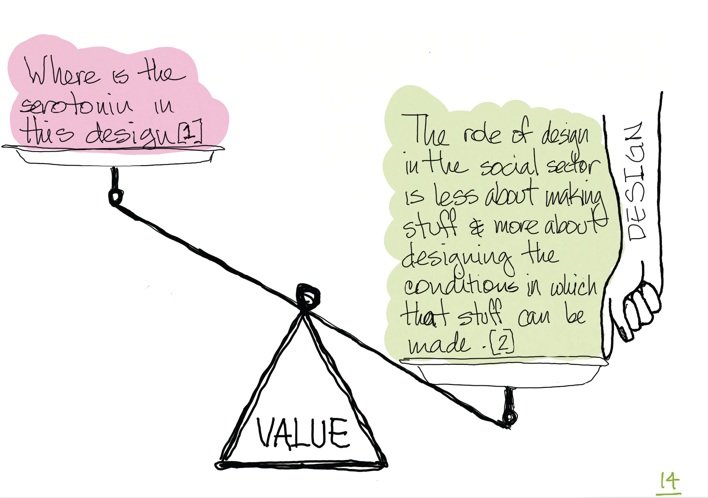

Re-orient

In her musings on how design designs us, Leyla Acaroglu calls design “…a silent social scripter that softly shifts and curates the values, opinions, cultures, and experiences of humans all over the world.” In this zine challenge, I wanted to explore the promises and power of technologies/companies/designers to bring us the world and remove us from the world we move in [and why]. There are many conversations about policy and systems that are vital for this moment. But I wanted to recall a simple and immediate tool of resistance present in our back pockets: the power to choose for ourselves how we will engage, re-orient, and navigate this. In her reflections on how to do nothing, Jenny Odell reminds us of the value of recharging. She shares a quote from David Abram that resonated strongly with me: “Only in regular contact with the tangible ground and sky can we learn how to orient and to navigate in the multiple dimensions that now claim us.” I concur.

For further reading:

https://medium.com/disruptive-design/how-design-designs-us-part-1-6583a9b61b57

https://medium.com/@the_jennitaur/how-to-do-nothing-57e100f59bbb

David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World

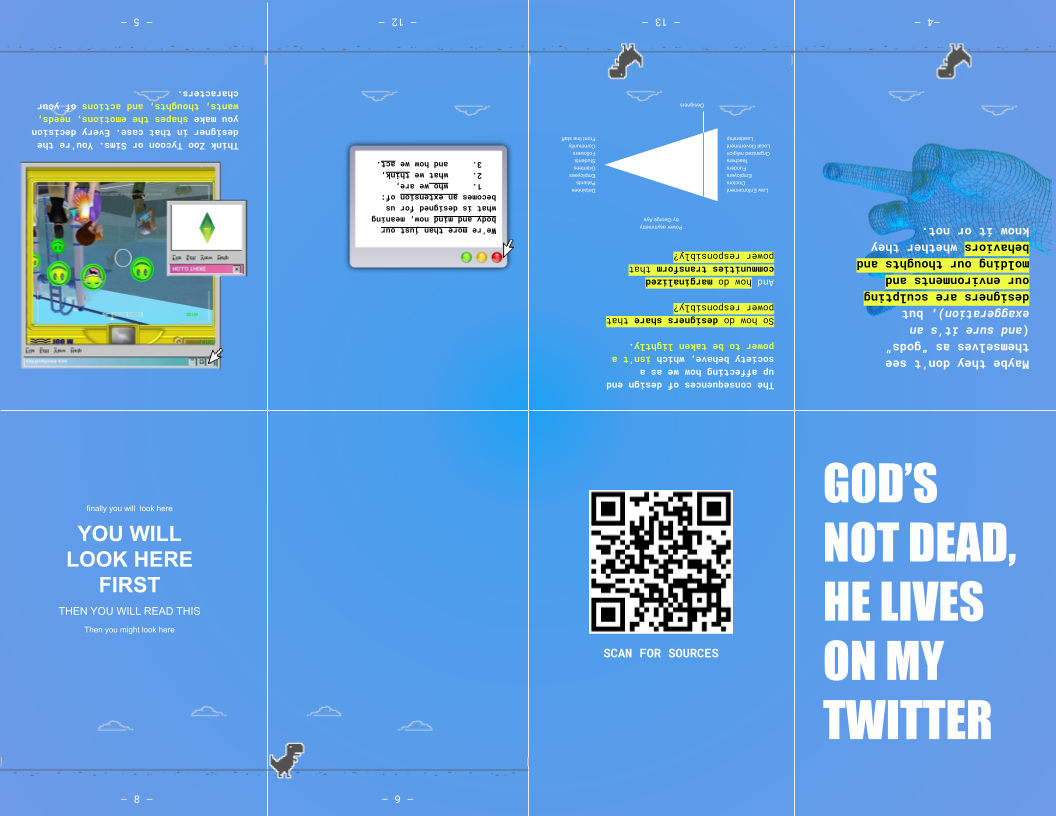

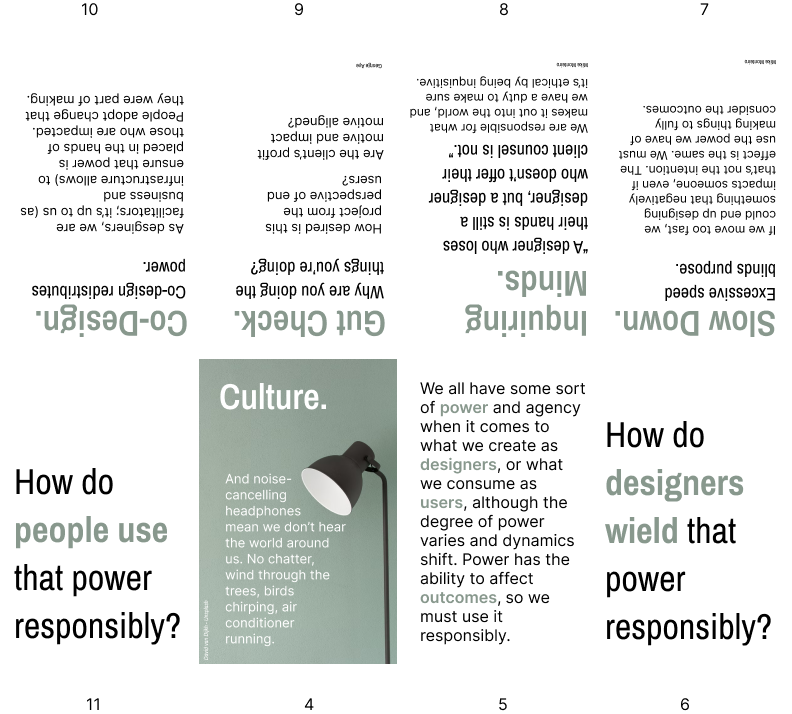

How do we use power responsibly?

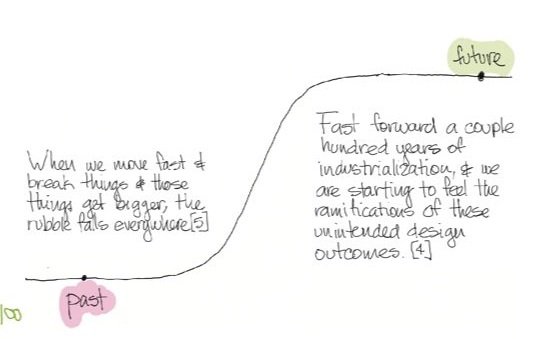

Over the last two weeks, we engaged with articles and videos about design, technology, and power. As a class, we discussed how they connect and how as designers we can use that power responsibly. Power affects outcomes. We as designers tend to have more power, and that power can give more power to the people we’re trying to help, or if not used responsibly, can lead to very negative outcomes. We design technology to shape our culture, and in turn that shapes us and what we continue to design–so we must choose to slow down and check the “why” behind what we’re doing.

For my second zine, I decided to create it on Figma to practice my skills for upcoming projects.

I also created it to be a mini zine to test my spatial abilities: 2.75” x 4.25”

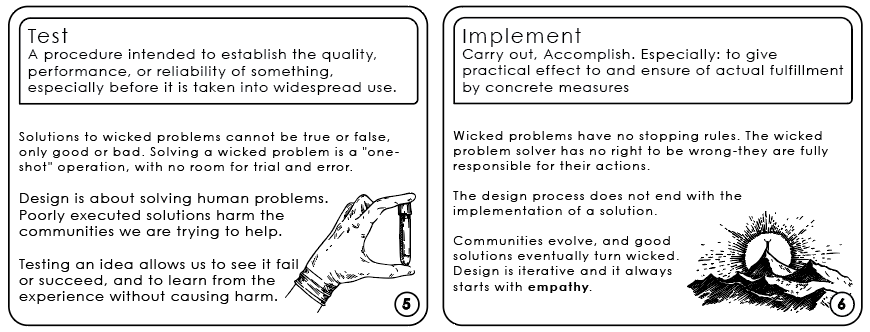

Please use the numbers as a guide to read the zine in order.

Zines: A Tool for Self-Expression

This was my first real zine (aside from our warm-up zine class activity), and I can see why people love them. Zines allows for self-expression and FUN. As someone who rarely partakes in arts and crafts, I decided to go the digital route and made my zine in Canva. I wanted to focus on creating something that was fun to look at while also guiding the reader to want to learn more. I also wanted the message of the zine to end on an optimistic note regarding the future of design.

If I were to do this project again, I would challenge myself to create a zine by hand. At the start of this project, I was envisioning creating something that looked like a Dr. Bronner’s bottle of soap (if you know, you know), and I sort of wish I had followed through with that vision. Given the time constraints, creating something by hand would have allowed me to focus on the message I wanted to convey rather than less important things like fonts, photos, and how to print the dang thing. All in all, though, this was a super interesting experience and I’m glad to know more about the zine world. ‘Til we meet again, zines!

What time is it? ZINE TIME!

Our first deliverable after 2 weeks of participating in our Q1 Public Sector, Innovation, and Impact course with instructor Christina Tran was to make our own zine – HOW. FUN.

The prompt was: What is design (thinking), and why should (or shouldn’t) we use it to tackle wicked problems?

Do I prefer this to writing a paper? Heck yes.

I like going analog, because my hands are doing more than just typing. It stimulates my brain in a different way, engaging in something more tactile as I’m processing and organizing information. By putting pen to paper, things feel exploratory, playful, and messy.

This is only the third zine I’ve ever made (second one being the zine we made to help introduce ourselves in the first session of this course, barely 2 weeks ago), but I can easily see this becoming a thing.

Need to get my creative juices flowing? Zine.

Mildly grieving the end of a great book, film, or TV show? Zine!

A friend’s birthday coming up, and we’re still stuck in this pandemic? ZINE.

Did I answer the prompt entirely? Maybe, maybe not. When I thought about what design was, I thought about what it meant to me, and how that interpretation had evolved.

I thought about past readings that have inspired and informed my ideas about design and its place in the world (as well as my relationship to it), such as adrienne maree brown’s “Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds”, in which she highlights the importance of connection, the 1:1 relationship, interdependence, adaptation, and challenging ourselves to reimagine what’s possible when we tune into the wisdom that nature affords us, inviting lessons from the principles and behaviors that exist in natural ecosystems. I integrated those learnings with work that we’ve recently been exploring and discussing in class, such as Anoushka Khandwala’s thoughts on what it means to decolonize design and Richard Buchanan’s “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking” (from 1992), in which he calls design thinking the “new liberal art of technological culture”.

Some common threads that surfaced for me were the importance of systems thinking (because we all exist and operate within different systems), learning to adapt alongside change (which is constant and inevitable) while maintaining compassion for ourselves and others, and challenging ourselves to envision new ways of being and creating – and then making that tangible somehow, by first putting new ways of being and creating into practice, one small (sometimes uncomfortable) step at a time.

So when it came to the zine, I wanted to express some of the words that were floating around in my mind; words I associated with how I’ve come to think about design, the principles that have influenced my approach (thus far) to designing, and the responsibility I feel that comes with designing products, systems, and services.

Of course, there’s only so much content a 3”x 5” zine can hold (part of the beauty of it!). There’s more to be said, and design is an ongoing conversation, so I welcome your reactions, questions, ideas, and provocations.

It was thrilling, it was fun, it was challenging… it was a tad bit rushed! It was inspired by others who have written things about design that resonated with me, and I hope this little zine, in some way, shape, or form, resonates or stirs something up in you.

…And here it is, my zine (hope you get a think/kick out of it!):

Design Thinkzine

My aim in this zine challenge was to distill the extensive topic of design thinking into the smallest format possible - pulling out what has resonated with me at this early point in my own design journey and finding my own words to communicate this to others.

To read more, check out:

1. Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse. Duke University Press, 2018.

2. Szczepanska, Jo. Design thinking origin story plus some of the people who made it all happen. https://szczpanks.medium.com/design-thinking-where-it-came-from-and-the-type-of-people-who-made-it-all-happen-dc3a05411e53

3. Buchanan, Richard. Wicked Problems in Design Thinking, Design Issues Vol 8, No 2, Spring 1992, The MIT Press.

4. Khandwala, Anoushka. What Does it Mean to Decolonize Design?: Dismantling design history 101. 5 June, 2019. AIGA Eye on Design. https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-design/#:post_81855

5. Design Justice Network Principles. https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles

6. Brown Tim & Wyatt, Jocelyn. Design Thinking for Social Innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2010.

Design thinking for a world of wicked problems

Over the past two weeks, our class has discussed the ideas of who can call themselves a designer and what design is. A recurring topic discussed was that design does not exist in school curriculums until college.

Design thinking transcends the field of design. It is a methodology that everyone should learn in the early stages of education—not reserved for those who can attend college. I created the zine below for people with little to no knowledge of the methodology. I hope this zine sparks curiosity and a new angle to solve problems with humanity at the center.

What is Design Thinking… the zine!?

Image to be read left to right, row by row.

Welcome! Please feel free to take a look at my very first AC4D creative deliverable…a zine that explores the topic, what is design thinking? In the first two weeks of our Theory class, we have been engaging with readings from authors that theorize human centered design, its capability to solve through co-creation, and its downfalls of unintended consequences and exclusivity.

My intended audience is anyone new to design thinking (hi!). I tried to capture the essence of some of the key theories we touched on in our initial reading, and best practices for inclusive design we learned about in modern readings. I wanted the reader to see the diversity in theory by seeing diversity in the ways the ideas were displayed (collage, word art, etc.) Let me know if you happen to think, “wow, design thinking looks like a field with a lot of diverse ways of communicating, and I want to learn more about it!” That’s what I was going for.

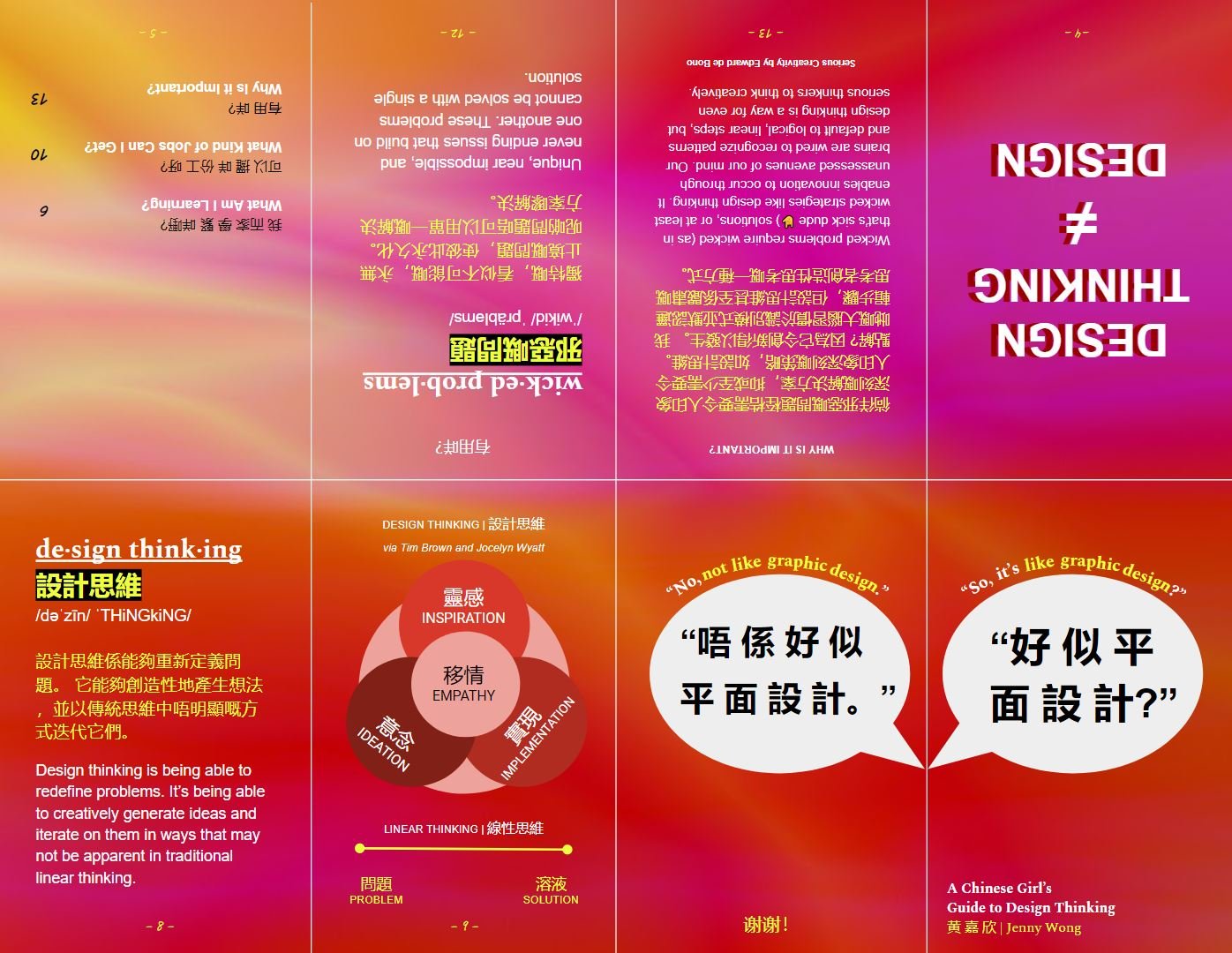

“So, It’s Like Graphic Design?” | “好 似 平 面 設 計?”

A Chinese Girl’s Guide to Design Thinking

I’m familiar with zines but have never made one myself, so I figured I might as well make one I can use on a daily basis. Design is hard enough for me to explain in English to friends and curious strangers on airplanes, so imagine me trying to do so in broken Cantonese to my parents. My dad calls me at least once a week, asking me to remind him what it is I’m trying to learn again. It’s both frustrating and shameful because Chinese is my first language, yet I’m not fluent enough to articulate these complex philosophies and thoughts. This is why “So, It’s Like Graphic Design?” was put into existence— so I can hopefully just mail one to my family members and they won’t have to ask me anymore. Feel free to print one out if you’d like by clicking on the link above. Click here for the video to teach you how to assemble the zine.

Most Chinese people read in Mandarin, but I unfortunately am not very confident in my Mandarin skills to go between English and Mandarin translations. To get some reasonable Cantonese translations, I used Microsoft Bing (because believe it or not, there aren’t many English to Cantonese translators out there). I can’t read in Cantonese at all really, so I relied on the text to speech function to listen to what was translated instead. My listening and comprehension skills are still lacking, but much better than reading or writing. I would also use speech to text, speaking in Cantonese, to get the correct characters if I felt like what was translated by the application was incorrect/felt awkward.

Honorable Mention: I was inspired by Clarence Kwan’s zine “Chinese Protest Recipes” that highlighted ways Asians Americans can support the Black Lives Matter movement while also sharing traditional Chinese recipes.

What the heck is design thinking?

As someone who is now taking my first “formal” dive into “what is design thinking,” I figured that many prospective AC4D students may not know what it is either. I created this zine to illustrate what design thinking is, and how it can be used to solve wicked problems.

Design Thinking Is…

Our assignment was to create a zine within the framework of this prompt. What is design (thinking), and why should (or shouldn’t) we use it to tackle wicked problems?

I wasn’t even sure how to make a zine, so I started there. After exploring popular formatting options, I came across the idea of folding the paper like an accordion from a zine review youtube video.

The questions of “what is design thinking” and “should we use it to tackle wicked problems” have been at the heart of our theory class for the past week, but I wanted to round out my opinion with supplemental writings. Doing secondary research on this history of design thinking, I came across Design thinking origin story plus some of the people who made it all happen by Jo Szczepanska.

The idea of creating a historical timeline of important innovations in design thinking immediately meshed with the accordion zine format. From there I was able to draft an outline of what would appear on each panel and then began designing.

Week 0 Musings

This week felt like a field trip to the beach. I got pushed by a few waves - of knowledge. I stumbled through sand - of confusion. The sun was warm and bright - like the students and professors. Now I am home, tired from all the adventure. Thinking about how much I loved it and how lucky I am to have found this brilliant and kind community.

The week went by fast. Every day, we learned a new design process and its relationship with previous processes. We learned about research interviews, synthesis, prototyping, and field testing. Below is a summary of my main takeaways.

Trust the Process: Situations will not always be explicit or within our control. However, we know steps and processes that help us move forward to gain clarity and confidence. We must trust that following those processes will lead us somewhere, even if it requires iterating.

Unlearning, to learn: I thought my experience as a recruiter would help during Design research. I was wrong. Researchers ask broad questions and listen, while recruiters tend to control interviews, looking for a wrong\right answer. So to become a better researcher, I have to unlearn being a recruiter.

Collaboration does not mean everything is a team activity: The purpose of collaboration is to work together to create. That does not mean doing the same thing at the same time or place. Teammates must learn each other’s styles and needs. Then give each other space to be themselves without the stigma of not being team players.

This is all for now. I cannot wait for class to start next week and do all of it again.

Hopping on the Learning Rollercoaster

When our cohort of eight started at AC4D this week, I didn’t really know what to expect. I knew the topics we’d be covering, and I knew I was excited – excited to learn things by doing, doing, doing (...and doing, doing, doing some more), meet people I could connect with and learn from, and challenge myself in new ways. As we wrap up our orientation, here are some things that I was reminded of this week:

Knowing what a growth mindset is, is entirely different than truly adopting one

Design is messy because real life is messy

Choose people over process when hitting roadblocks as a team

Practicing a Growth Mindset

Having been in the learning and development space for awhile, as well as playing the role of manager and coach in different jobs, I was pretty familiar with Carol Dweck’s concept of growth mindset. In short, growth mindset is the belief that our skills and behavior aren’t fixed, and that if we put something new into regular practice, we’ll eventually become better at it. Not super revolutionary when you think about it, but it’s way easier said than done.

Growth mindset influences how we deal with the challenges and discomfort that come with learning (especially as adults, when many of us tend to be a bit more resistant or stubborn about changing our existing habits), and therefore, how effective we are at picking up something new.

This week during orientation, we were put into small groups to experience a design process together, “thrown into the deep end” style – meaning, our facilitators took the design process that we’ll be practicing and refining during our time at AC4D and accelerated it, condensing it into five, jam-packed days.

Unsurprisingly, I found myself feeling scattered, rushed, uncomfortable, confused, and frustrated in different moments throughout the past week, especially when it came to understanding how my two teammates’ different ways of communicating and collaborating came into play. As we weren’t given a lot of time to get to know each other before working on our assignments together, this likely compounded some of the discomfort and frustration I experienced.

However, we’re more likely to learn and gain insight from experiences that elicit strong emotions from us, particularly when those experiences are painful, so reminding myself to maintain a growth mindset when things got a little challenging proved to be helpful. It was a great reminder to trust the process, do my best to exercise patience (with myself and others), and be open to what unfolds. It was also a great reminder that knowing what a concept like growth mindset is and how to describe it doesn’t necessarily mean we know how to demonstrate it – and that being willing to engage in practice is the most important part, because that’s when we can understand it best.

Messiness in Design Reflects the Messiness in Life

Going into AC4D, I was aware that design was messy. As we went through the different steps of the design process, that became even more apparent (and yes, at times annoying). While I’ve gotten fairly comfortable with adapting in new environments and navigating through ambiguity, that doesn’t mean I enjoy these things, especially in the moment. I’m constantly trying to make sense of what I’m experiencing, often seeking clarity (where there may be none), creating structure where I can, and wanting more time to process and connect the dots.

Diving into the design process with my fellow classmates, the “dots” weren’t always clear to us. I wondered whether this was by design (how meta!) or just inherently part of the process. There were moments when I felt like dots were missing entirely. As frustrating as this was at times, I compared the messiness I was experiencing to the messiness in the real world and reasoned that the process was simply mirroring what we all go through in our personal and professional lives. There are many ways to approach tackling the problems we’re faced with, and no matter what approach we take, the messiness is pretty inevitable. As designers, we’ll be designing things for real people with beautifully complex, nuanced stories and lives, so it’s no surprise that design is messy, because life is messy.

People > Process

This past week has also reinforced to me the value of simply listening to people’s experiences and stories in the design journey, and I don’t just mean the audiences I’m designing for. Design is rarely a solo adventure, and to me, a critical part of successfully designing a product, service, policy, or system is how effective I am at collaborating with others.

This is, of course, not unique to the field of design. Collaborating with others in our work and our jobs is just a part of the process. But how many of us genuinely invest in establishing some level of trust with those we work with, and how might a product (or service, policy, or system) end up even better if we gave greater thought and care into balancing building trust with our collaborators with the process of doing the work together?

I mentioned earlier that I experienced some discomfort this past week upon being thrown into new challenges with new people I hadn’t really gotten to know beforehand. There were times when I noticed my own frustration getting in the way of exercising patience with others, or when I was more focused on getting to the goal than inviting others to talk things through with me, and when this happened, I did my best to slow down and refocus my attention on the dynamics and energy within my group. Yes, it felt a little messy and uncomfortable, but in the end, we always arrived at a greater place of understanding and, I think (I hope!) trust. This is something I’m still working on, and will continue to work on beyond AC4D. In the meantime, I’m grateful to have the opportunity to do this with the seven other designers-in-training over the course of our program.

To sum it up, what the past week highlighted for me is that design doesn’t happen in a neat, straight line because our lives don’t happen that way. And when I’m experiencing tension, whether internal or external, connecting with people with intention will consistently bring me back to where I need to be – a place where empathy, creativity, and growth can thrive, despite being in the thick of a little chaos, confusion, and uncertainty.

Design Research 101

If there was one aspect of the AC4D program I was looking forward to most, it was getting a chance to implement the design research process. What is design research? It is learning from people in the context of their lives to obtain emotional insight, build narrative, and create value. In our AC4D orientation week, we focused on bite sized lessons followed by hours long working group sessions to build our own “fast and furious” attempt at design research. Here’s my understanding of the process paired with some insights gained from our directive: explore the topic of mental and physical health of frontline workers.

Step 1: Identify participants and develop a focus

In our respective groups, we gathered a list of frontline workers we know and love to talk with about their experiences. Our group consisted of healthcare workers (doctors, residency students, a dentist, a physician, a pharmaceutical worker, and a physical therapist) as well as a vaccine manufacturer. Our group brainstormed open-ended questions to develop a focus, which became we are researching how the relationships that frontline workers have (both in and outside of work) influence their physical and mental health.

Step 2: Create questions to gain insight on the research focus

Timed brainstorming sessions became the method of choice for our group this week. Developing a list of open-ended questions was a step that frankly deserved more time than we had to give. But when the theme of orientation is “fast and furious” – deliberation falls by the wayside. We decided to ask three key basic questions and developed a series of follow up questions in response. We wanted to understand a little about the following:

How healthcare workers spend their time (and wish they could spend their time) between shifts.

Who is important in their lives, and how work impacts their relationships with those people.

Who they work most closely with and how that relationship has changed with covid.

Step 3: Interview the research participants

In one afternoon, we interviewed eight participants back to back, pushing the limits of what a Sunday afternoon typically looks like. With one interviewer and one notetaker, we held short but meaningful conversations with these frontline workers. Our follow up questions managed to dig a little deeper, however we ran into a few instances where interviewees were asking us to clarify what we were looking for. However, I’m learning that designers are really working from a mindset of “no right answers,” so in order to get genuine “nuggets” of information from their participants, it is necessary to reassure them that whatever comes to mind is most helpful. Another trick we learned was to ask someone to tell us about a time when. For example, after asking “who is most important in their lives,” we asked the follow up, “tell me about the last time you spent time with them”. Overall, the value they provided helped us gain some valuable insights that we took to the next stage of our process.

Step 4: Synthesize insights based on interview “nuggets”

After reflecting on main themes from each interview and transcribing all interviews, we had a very large stack of printed “utterances” (or statements from our interviews). We learned a bit about pairing off statements with an “inferred likeness” and how to develop a connection statement - or what bonds those two statements. After separating many of our utterances, we were able to see several main themes develop. Some of ours included:

Participants long to be with family

Shared experiences sustain the healthcare workers we talked to

The toll of work can cause loss in relationships

Coworker relationships have become integral to their daily survival

From these insights, we could see some of the joyful and difficult aspects of the relationships that our healthcare workers sustained. We understood that in all cases, they relied heavily on several key people in their lives; and in some, that their co-workers had a shared understanding of working on the frontlines that was irreplaceable.

Step 5: Develop provocative insights based on your insights

The first piece of developing provocative statements was asking “why” following each insight. Then, zeroing in on a potential answer to that question, which can serve as a jumping off point for the next step in the process. The following questions were leveraged into (semi) provocative statements that allow us to begin to understand why our interviewees felt a certain way.

Why do participants long to be with family? They can be themselves and feel comfortable around family.

Why do shared experiences sustain the healthcare workers we talked to? They see some shit that the rest of us don’t understand because we don’t live and breathe it like they do.

Why does the toll of work cause loss in relationships? It is painful to lose a piece of yourself when giving an inordinate amount to your job.

Why have coworker relationships have become integral to their daily survival? Coworkers are a part of the team and help shoulder the burden.

Step 6: Develop many ideas that can address your provocative statements

At this stage, we had a lot of great insight, a few provocative statements, and a long way left to go. We used timed brainstorming once again to come up with nearly 300 ideas that we liked to act as solutions to our provocative statement. Here’s the secret: not all of them were good. In the “fast and furious” spirit, we developed many really bad ideas such as a petting zoo to help boost the morale of healthcare workers. With our few (potentially) good ideas, we placed them in a grouping as top choices that could be developed as actionable prototypes.

Step 7: Prototype your top idea and user test

After we finally narrowed down our top idea - a quick and easy way for healthcare workers to thank their colleagues. With the amount of time we had left in our orientation, we opted to keep our solution simple - an interface on healthcare worker computer systems that would allow e-card thank you notes to be sent between colleagues and an icon on the computer/system to display a thumbs up so healthcare workers could be reminded throughout their day of the positive notes they have received from colleagues. Ultimately, I know we will experience a much fuller scale iteration of future projects at AC4D, and I really look forward to understanding how prototypes are developed and refined in that process.

Overall, this initial orientation week has left me with a lot to look forward to throughout my time at AC4D. I am really interested in diving into this process with multiple iterations, and in all its messiness, retaining some valuable insights that can carry us forward to positive solutions.

Top Three Orientation Takeaways

1. Having a growth mindset is an ongoing process

Throughout this intensive 5-day bootcamp/orientation, I have realized that I can’t just snap my fingers and have an ongoing growth mindset. Having two hours to prepare questions for frontline workers about their mental health and then being thrown into the fire with interviews is uncomfortable. Coming up with 300 ideas overnight is uncomfortable. Choosing a product concept to test with users within 15 minutes is—you guessed it—uncomfortable! So, what have I been learning? That truly having a growth mindset requires you to check in with yourself consistently. As someone coming into design with a fairly unrelated background, this experience is going to test me. It’s going to require me to be brave and to challenge myself to test the limits of what I previously thought I was capable of. What drew me to this field was the potential for creativity. It’s a muscle that I haven’t gotten to flex too much in the professional world, and with this opportunity comes the work of showing up in an honest and open-minded way every single day. I can’t wait to dive in.

2. Active listening while having an agenda

I was shocked at how challenging the interviewing component of the design process is. I figured, “I’m an empathetic person—shouldn’t be too hard.” The truth is that design research and interviewing does not just involve having a conversation with someone; it is about keeping in mind what you are setting out to learn and attempting to guide the interview in a way that highlights the question at hand. I found myself focusing on which question I would ask the participant next, which made it nearly impossible to hone in on the details of what they were saying in order to guide the interview to the next level of depth. Experiencing this component of the design process at the beginning of the program (and before we really know what we’re doing) was eye-opening. It allowed me to recognize the importance of staying in the present moment to fully understand what the participant is saying.

3. Progress, not perfection

“The perfect is the enemy of the good.” A lot of us are perfectionists, and a lot of us feel like it’s one of those useful yet crippling double-edged swords. I think I’ve been a perfectionist since the day I was born. I have memories of having “braid wars” with my mom, continuously undoing her hours of hard work and telling her, “they’re not quite right.” Or coloring in my coloring book (which was supposed to be fun) and ripping out a page any time I made a mistake. Over the years, I’ve had to let go of some of this. It’s just not possible to do all the things you want to do if you’re trying to do them perfectly. I’m excited that being a designer is going to force me to shed even more layers of this tendency. These past five days have taught me that what matters as a designer is creating something that’s useful for people. The rest of the details are—well—details! The importance of hitting a deadline and covering the breadth of a topic outweighs attaining perfection, especially at the beginning of the design process.

Q0 — An Understanding of Myself and Others

This first week has already taught me so much about myself and design through expected and unexpected aspects of this one year immersive program. I expected to learn about UX design and best practices to achieve an end product, but I never expected the program to listen and talk about the emotional and mental blocks that can come from this specific field of work.

Having a Growth Mindset:

These past few discussions we’ve had about engaging in a growth mindset is something I’ve come across before and have always struggled to grasp. It’s not that I don’t understand it, but more so it’s extremely difficult to implement in my daily life, especially now at AC4D. As the youngest of the group, I automatically assume I’m the least experienced and constantly feel the need to prove my worth to others. I haven’t let go of this self-concept, but our group discussions about growth mindset showed me that I’m not alone in these thoughts. Knowing that we’re still all learning, whether you’re an expert in the field or a complete beginner, is reassuring. It helps me reframe my current, more self-deprecating mindset to one that promotes acceptance of the unknown to foster growth and development. Ultimately, having a growth mindset makes you more resilient to uncertainty and forces you to get comfortable with failure because, if you let it, it can only make you stronger.

Understanding Your Team:

I’ve worked with teams in the past and it’s never been as involved or close knit as the group I’ve spent the past three days with. It’s insane to think about because I’ve only just met these people, but I’ve already found myself better understanding how others tackle problems. My group in particular spent a fair amount of time learning how we each deal with problem solving, stress, and uncertainty, as well as our differences and similarities in communication styles and thought processes. In my experience, teams tend to jump into trying to find a solution before understanding how each other works– I’m guilty of this. This can lead to uncooperative group dynamics and frustration that isn’t productive or helpful to reaching a goal. I felt this frustration at times in my group, but once we stopped and talked about what was frustrating us and why, it put into perspective how we each process thoughts, ideas, and emotions. There were times when each member of my group would have a different concept of what a task or piece of information meant, so talking it out to make sure we were all on the same page was crucial for us to move forward. Having these discussions are necessary for success and emphasizing its importance has been eye opening for me in the midst of the design process.

Get Out Of Your Head:

I’ve always been someone who keeps their ideas in their head because I’m either too afraid or lazy to actualize it. These past three days have forced me to take whatever musings I have in my mind, no matter how seemingly silly, and put it out in the world, whether that’s on 300 Post-It notes or a messy low-fidelity wireframe on paper. I think of it almost like the phrase “no regrets” because you’ll never know if you don’t at least entertain the idea and put it into some form of existence. Throughout these three days, I’ve learned to not overthink during the beginning stages of the design process and to just throw things at a wall and see what sticks (literally and figuratively). This relates to testing as well because your perception of an idea may very well differ from those of others– you’ll never know until you try. Visualizing my thoughts helps me move forward. Sure, maybe the notion did suck or maybe it didn’t, but at least now you know and won’t keep thinking “what if”.