Power and Co-design: Bridging the Gap

In our Theory class, we’ve been exploring the topic of power within the context of co-design. That’s not only a mouthful… it’s a lot to wrap one’s brain around 🤯🤯🤯

Questions arise such as: what is the designer’s role in balancing power dynamics? and what degree of participation do our stakeholders actually have compared to what we want them to have? These are tough questions to answer. Luckily, we can apply one simple tactic to lessen their ability to make heads explode: awareness.

Per Lauren Weinstein’s Shifting the Powerplay in Co-design, power is the ability to influence an outcome. Co-design is a commonly used method intended to bring people affected by an issue into the process of understanding the problem and designing a better response. Bridging these definitions, we can become more easily aware of power’s influence in regards to co-designing solutions to complex problems. Let’s take a look at an example:

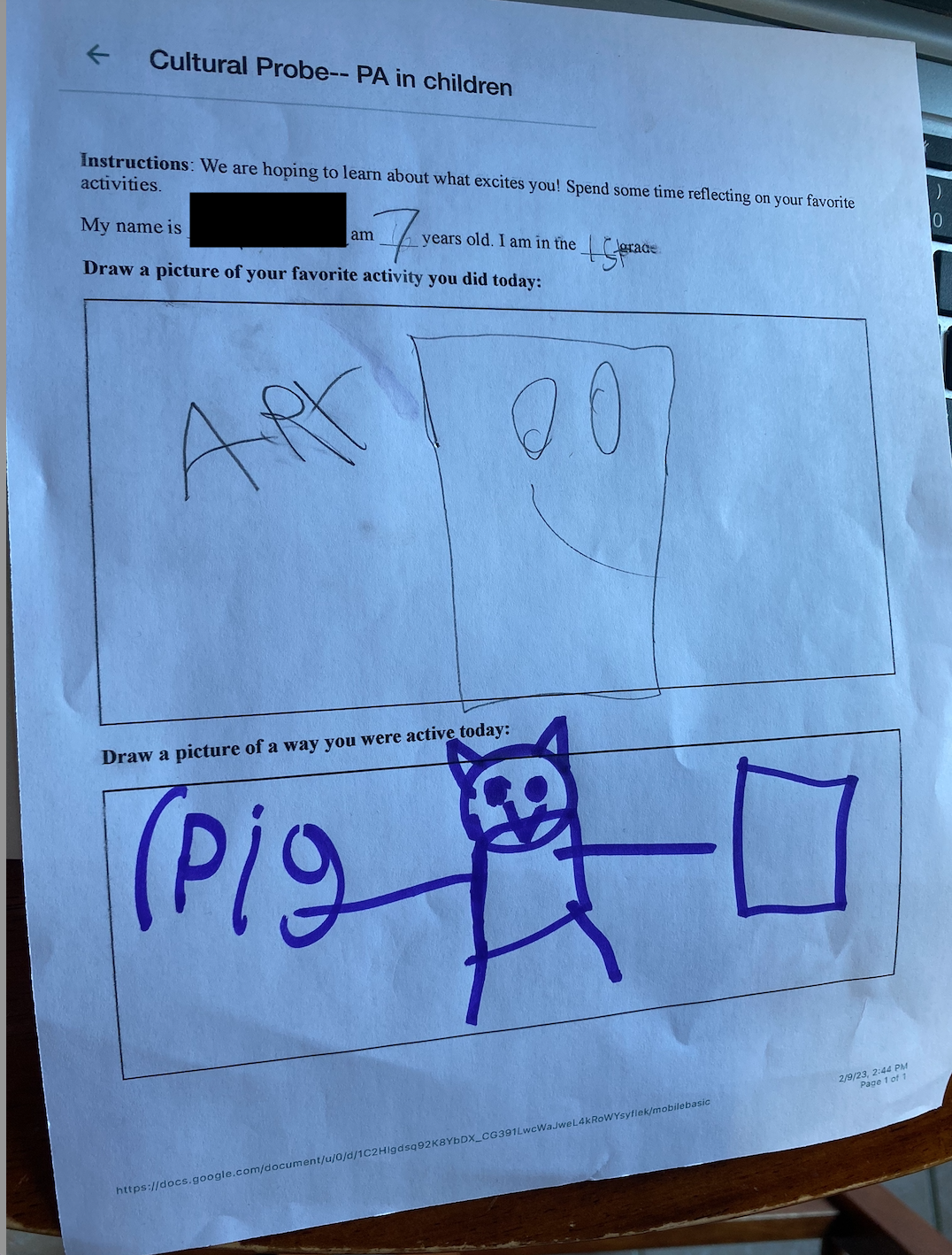

Recently, Jess and I have been working on our research project which is focused on the barriers families face in relation to kids’ physical activity. We interviewed multiple parents and several school administrators (notably, PE teachers) and learned a lot about these barriers. Some were obvious, some weren’t. In regards to power and co-design, however, we learned that we overlooked the core of our research: the kids.

From the perspective of the parents and administrators, we have the parameters of what physical activity includes (duration, setting, budget, etc.), but we don’t have the actual activities that kids want to take part in within those parameters. We neglected the fact that kids tend to have little to no power when it comes to decisions being made about their lives, effectively leaving them out of the co-design process.

To balance the power dynamic, kids must have a say in what physical activities they participate in, as well as a say in the outcomes of those activities.

For example, Amy (below) was active when she performed in The Three Little Pigs in her theatre class. She had fun, she danced and sang, and she got to dress up like a pig.

Kids’ definition of physical activity may not align with that of adults… and that’s okay.

Ultimately, with a redistribution of power, adults can co-design activities with kids that satisfy everyone’s needs. (Redistribution of power in this case could be seen as awareness.) Maybe kids aren’t wanting to exercise in the traditional sense, but including them in the co-design process can still produce the outcomes everyone is wanting: happy, healthy humans.

A Case for Design

Design is not something we can choose to care about or not - we’re living in a world intertwined with things, mechanical and smart, analog and digital, that have been designed by us and in turn design us through our behavior, over time. These things and processes are something we have to engage with no matter what. We don’t really have much choice there.

The most interesting thing about Design, to me, is that we’re all designers, because we do have a choice in how we participate in the world. Everyone influences their small personal sphere, community and society. These are some of the choices we could make:

Make a choice to design (create products and services) in a way that improves our experiences of being part of a society.

Make a choice to design in a way that serves only a few, in the short term and potentially (very likely) harms some people, whole communities or humanity itself.

Make a choice by choosing to do nothing about things we critique and complain about. Sit back and watch humanity devolve.

Become an anarcho-primitivist. Yes that’s a choice too and an infinitely more interesting one than choosing to do nothing.

Another very interesting thing about design is the scale at which it exists. Design is about everyday things and it is also about the complex frameworks of society. Applying the tools for designing well are necessary at both levels.

Scale: Design of Everyday Things

This is a fictional object but the point it’s making is that if an everyday object is difficult to use or gets in our way - it’s not the user that lacks understanding but the design itself.

This is a badly designed door. You might have seen one like this or many other kinds of badly designed doors. Doors shouldn’t require any intentional thought. They should be intuitive to use! We should be able to continue with our prefrontal cortex activity contemplating whether it is the meaninglessness of life or how to bring down patriarchy without the rude interruption of a door that didn’t open when we interacted with it the way it seems natural to.

People named these doors Norman doors and they’re everywhere. Vox made a funny video about that.

Don Norman studied the psychology (design) of everyday things such as doors that are difficult to open, light switches that make no sense, shower controls that are unfathomable.

Any everyday object that creates unnecessary problems. These problems sound trivial, but they can mean the difference between pleasure, and frustration. The same principles that make these simple simple things work well or poorly apply to more complex operations, including ones in which human lives are at stake.

– Don Norman

Scale: Design of Complex Systems

Design is also about systems that are essential to our well being and existence.

We are already surrounded by processes that design products, systems and behaviors.

A well known process is the scientific method and when applied towards continuous improvement it can look like:

Below is a case study of how Mayo clinic applied their clinical approach for testing drugs to testing relationships and people facing aspects of care. Mayo clinic’s epiphany was about the relevance of the design process that they were already using (scientific method) for another system.

Let’s talk about one of the technologies closest to us: semiconductors. These power our lives and make possible all the devices that we live with; some of these that we aren’t even aware of! Some devices are right in front of us but we don’t actively think about them because we don’t need to, as long as they’re doing the function they were designed to do - well and consistently.

In semiconductor research and development, new chips are not built on a whim or design opinion of a single person or even a single team. There are as many as a 100 layers on a single chip, each requiring deep understanding of the subject matter and each layer interfacing with the next.

Even a device as simple as a smart thermostat has a lot of complexity. There are hardware, firmware, software components - each layer of engineering was made possible because of decades of innovations making the next set of innovations possible. Can you imagine the amount and variety of work that goes into designing a complex piece of technology that in the world serves a simple and dedicated function of regulating its environment’s temperature? The ‘smart’ part allows users to set schedules or routines and forget about it. The device handles this function for them from then on.

If there are even the smallest things that don’t work right - it could mean constant irritation for the user, a complete failure of its intended function, or at its worst it could put the user in danger.

When you open up apps that you use on your (smart) phone everyday for communicating and coordinating day-to-day activities between your household, school, work, etc - If something gets in the way of you accomplishing a task, it will be noticed by you right away. Even the smallest of bugs can disrupt and trigger a chain of annoyances that most users do not expect to live with today.

Software fixes and updates are quick to roll out and aren’t that costly and that’s why the world of Software runs on the principle of ‘move fast and break things’. The same philosophy can’t be followed across other platforms of engineering though. Firmware and Hardware are very, very costly to iterate upon and the margin of error needs to be less than the margin that would be perceivable by the user.

(Note: There are exceptions - mission critical projects like space travel where software needs to have a margin of error similar to traditional engineering.)

As we get closer and closer to those layers of tech that are slower to change and correct, we’ll find that more work, collaboration, expertise, prototyping, testing and care goes into it.

Does the same happen in the service sector? Some services that power our lives are:

Healthcare

Education

Social Security

Unemployment Assistance

These systems that are painfully slow to change and improve - have these been built with the same type of deliberation, application of rigorous processes and understanding of all components that fit together like a puzzle?

No, I don’t think they are.

But I’d urge for us to expect them to be and advocate for them to be and make it so they are.

Now, I could be wrong about this statement and the failures might exist despite a rigorous and deliberate process but in either case there are specific improvements that could be made.

One pessimistic reason one might give for not attempting to design better systems is that humans are a big factor in these systems and that makes these systems less reliable and more unpredictable. A transistor will do exactly the same thing it’s been designed for, for its specified life time. Humans though? We are more complex and less consistent. I have to say though - that’s a feature not a bug and we should use the fact that we’re not robots (though we are programmable) to our advantage as well :) but for now, let’s continue focusing on the challenge that this feature adds.

How can a process help design better systems meant to serve our societies?

I agree with the view that we are a product of our environment and our experiences. So, we can continually influence ourselves and continually improve ourselves using our environments and experiences.

If we find ourselves being dissatisfied with people who are are the interface between us and the complex systems and they in turn are dissatisfied with the people who hold certain gates in those systems, having more power than them, and so on… we must consider what are the systems that are shaping people to behave in ways we disagree with as well as what are the problems that hinder people from behaving in the ways we want them to.

If we are to consider applying a design process to improve services in our communities, what might that look like?

References

Don Norman, Design of Everyday Things

Alice Rawsthorn, Hello World

Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice

Michelle Jia, Who gets to be innovate?

Other Readings

Ian Paul, What is a 5nm chip?

Sebastian Romero Torres, How difficult is it to design a next generation one?

QingPeng Wang, Accelerating Semiconductor Process Development Using Virtual Design of Experiments

Market v. Design Research: What Ultimately Makes the Difference?

In his article, “The Value of Synthesis in Driving Innovation,” Jon Kolko makes an interesting distinction between market research and design research [1]. Whereas market research is equipped to simply predict future behavior, according to Kolko, design research goes further by helping individuals find inspiration for design.

My rationale for why this happens actually stems from another article written by him, “Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis,” in which he juxtaposes various forms of reasoning (e.g., deductive v. inductive reasoning — i.e., reasoning from the general to the specific v. reasoning from the specific to the general). In that article, he posits that design synthesis — the process that bridges the gap between design research (problem understanding) and design (problem solving) — is underpinned by a form of reasoning called “abductive reasoning,” which is when a designer makes a “best guess” or inference/leap from what is to what might be.

Source: Kolko, "Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis" (pp. 19-21)

As far as I can tell, both market and design research methods employ various means of sensemaking. But, the underlying reason why design research is able to inspire while market research can only predict, I believe, has to do with the form of logic that underpins each research method. Market research employs inductive reasoning: it begins with a hypothesis, then tries to make a broader claim (or theory); but it stops there, which is why it can only predict behavior. Design research, on the other hand, is underpinned by abductive reasoning: it allows the researcher to draw inferences and make “best guess” leaps; unlike inductive reasoning, abductive reasoning allows for the creation of new knowledge. And it is this new knowledge — these new insights that are created — that provide the inspiration for design (problem solutions).

References

[1] Jon Kolko, "The Value of Synthesis in Driving Innovation" (pp. 38-40)

[2] Jon Kolko, "Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis" (pp. 19-21)

A Case for Design: Exploring the Vision Plan for Zilker Park

In this blog post, I make a case for the design process and explain how it aids anyone looking to create a product, community space or program. The objectives are to understand the phases of the design thinking process, how it can cultivate deep trust and empathy with the community and how it is beneficial to the community and the people funding the project.

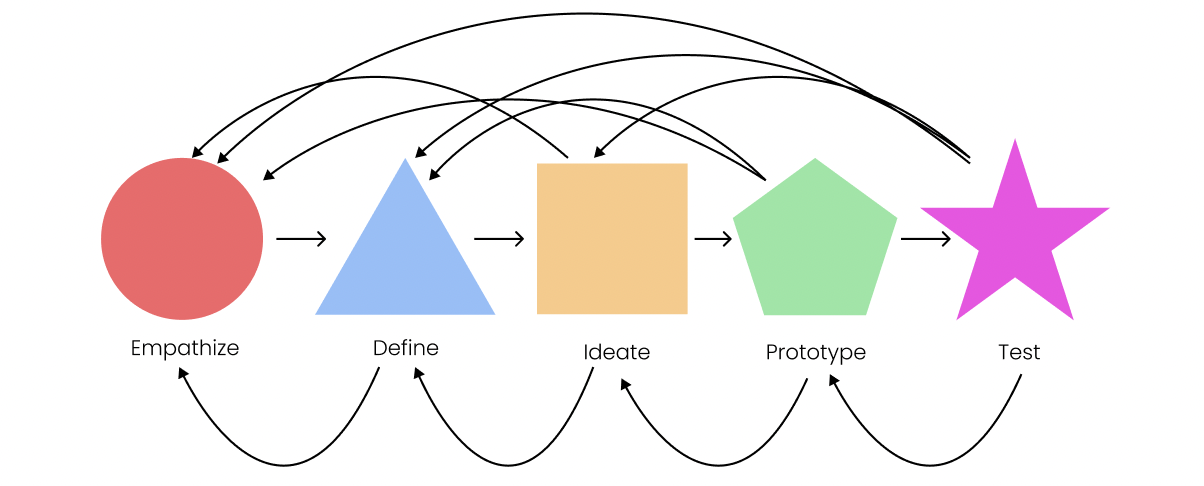

Below is a diagram representing the design thinking process, demonstrating that it is a non linear process.

To explain this process in detail, I am using a relatable example for people living in metropolitan areas. In Austin, there has been a lot of discussion about a vision plan for the future of Zilker Park (a well loved park in Austin). “Zilker Metropolitan Park Vision Plan is a community-driven planning process to establish a guiding framework for the restoration and future development of Zilker Metropolitan Park.” Below, I will run through the phases of design thinking related to creating the future of Zilker Park and explain why this process is beneficial.

In this phase, it is important to engage and empathize with the community who is at the center of what you are designing and understand people’s needs, challenges and desires related to the experience. The designers working on the future of Zilker focused on learning what prevented people from going to the park or fully enjoying their time there. This was done through surveys, meetings, and discussions with people in the community. In these forums, members of the public were able to share their thoughts.

Next, designers needed to define the problem the community is facing when trying to enjoy Zilker Park. What are common challenges, needs, desires that people are experiencing? The problems should always be focused on the community. Designers found that one common problem people faced was the lack of parking and difficulty getting to the park due to traffic.

Here it is beneficial to come up with as many possible solutions as possible for the defined problem. Designers working on the Zilker Vision came up with ideas for increasing parking, bike lanes, pedestrian bridges, shuttles etc.

In the prototyping phase, it is helpful to initially create a version of the solution that is inexpensive and easy to test with the community, something that can be iterated with feedback. The designers for the Zilker Vision created a map of the park with a detailed description of their proposals.

Here the prototype is tested with the community in order to get feedback. An important part of this step is finding out if the solution is actually what people want. You will likely need to repeat previous steps in the process, to come up with the best possible solution. The prototype for the Zilker Vision was shared online with the community with an attached survey and section to make comments. They were able to find out what solutions people liked, what people would not want to see for the park and why.

The design team working on this vision of Zilker Park are now in the process of iterating this design proposal with feedback from the community. The benefits of going through the design thinking process and repeating steps as needed is that you will get an end result that the community wants and will use. People feel listened to in the process and it fosters trust between the community and institutions. It also is beneficial to the organization funding the process because they are not wasting excess time and resources on solutions that people don’t want. Spending more time in the design process, will minimize problems you may face in the future.

In summary, the design thinking process helps solve problems benefit both the community and the organizations. It is an important tool in defining and achieving our goals.

What is Design? A case for Design

This was a big one, Design encompasses so many areas that when I started to narrow down the focus for creating this case, I felt I wanted to talk about so much and there was so little time. Funny enough, in the Design Thinking process we are commended to take decisions, choose which problem -or part of it- we want to tackle.

So as I jotted down some ideas for creating a case for Design, I knew I wanted it to be visually engaging and not take it so seriously as I tend to do.

Day to day designing

I believe everyone is able to be creative, if you look at peoples lives, we’re often finding ways around to accommodate our lives, or just make them easier, to make ends meet.

Take as an example those famous ‘life-hacks’, those are nothing more than workarounds and by doing that we’re designing an easier life (up to a certain extent).

What do we call design?

This was one of the main blocks of what I wanted to share, there are so many conceptions about design, what’s on the surface for most people is to ‘make things pretty’, but I believe thats only a small part of it, we, as designers are here to design an experience that exists to solve a problem.

We are here to solve existing problems

This is where research comes to play, we shouldn’t assume what the problem is without talking to the actual people being affected from it. It’s easy to assume others problems from our point of view, take as an example what happened with a program that wanted to give out free menstrual pads to girls in poverty Africa, the people who ideated this ‘solution’ thought the problem was lack of hygiene supplies. That problem statement came from a first-world lens, in which you are able to go to the store and buy them, but it did not take into account that schools in Africa did not have proper restrooms, trash bins to dispose those and also that there is also a temporal disability that can happen when going through your period that might disable you from being able to attend school altogether (i.e, getting sick, having pain, etc.)

Disclaimer: Even as I’m writing this I can only speak from my (non-existing) experience and research on this specific topic.

So to summarize, the problem was not the lack of hygiene supplies. And this is a clear example of why we need to get to the root cause of the problem.

Case for Design

During my research of the case for equality in design justice, I reviewed multiple sources that contended the basis for equitable design is the acknowledgement that 1) living/designing in any society means you will interact with multiple systems of oppression regularly and 2) all design is political in either it’s rejection or upholding of these systems. In essence nothing exists in a vacuum, and what we create will have social impact regardless of our intentions. As designers we are responsible for investigating our own culture and history within everything, and it’s important to be cognizant of whose historical narrative we pull our understanding of the world around us from to ensure the impact of our design is actively positive, not passively negative

“Design either serves or subverts the status quo.”- Tony Fry

While researching my case for design I also found this incredible, tonally disappointed coverage of the opening of the Austin Metro. The article does a really nice job of inadvertently pointing out all the ways in which the design process for the Metro just didn’t happen. It was also a very neat little case study in how the user is aware of when “shortcuts” are used to solve problems. “With Modest Expectations, Austin Opens Rail Line After Years of Delays” (Freemark, 2010, The Transport Politic)

Where do we grow from here?

When talking about systemic, complex problems in the world I’ve found myself gravitating towards discussions of how we would rebuild an ideal society, from scratch. It’s always a lively discussion to talk about what we wish already existed in the world. It’s also quite satisfying learning a little bit more every time, tracing back the roots of the current system with every new piece of information and perspective. Eventually though, the discussion comes around to the action part and it goes something like

‘We have an idea of what an ideal society would look like but in reality there is no building from scratch or going back in time, so what can we do?’

At that point after the lovely shared existential depression, my friends and I punt the discussion to another time. Once again.

I’m here at AC4D for the year-long immersive program seeking the skills and the community to help take some concrete steps after all the feel-good critique of the current systems is over.

We just got done with the orientation week at the AC4D and were thrown into the deep end to get a taste of all the steps of the process we’re going to learn here.

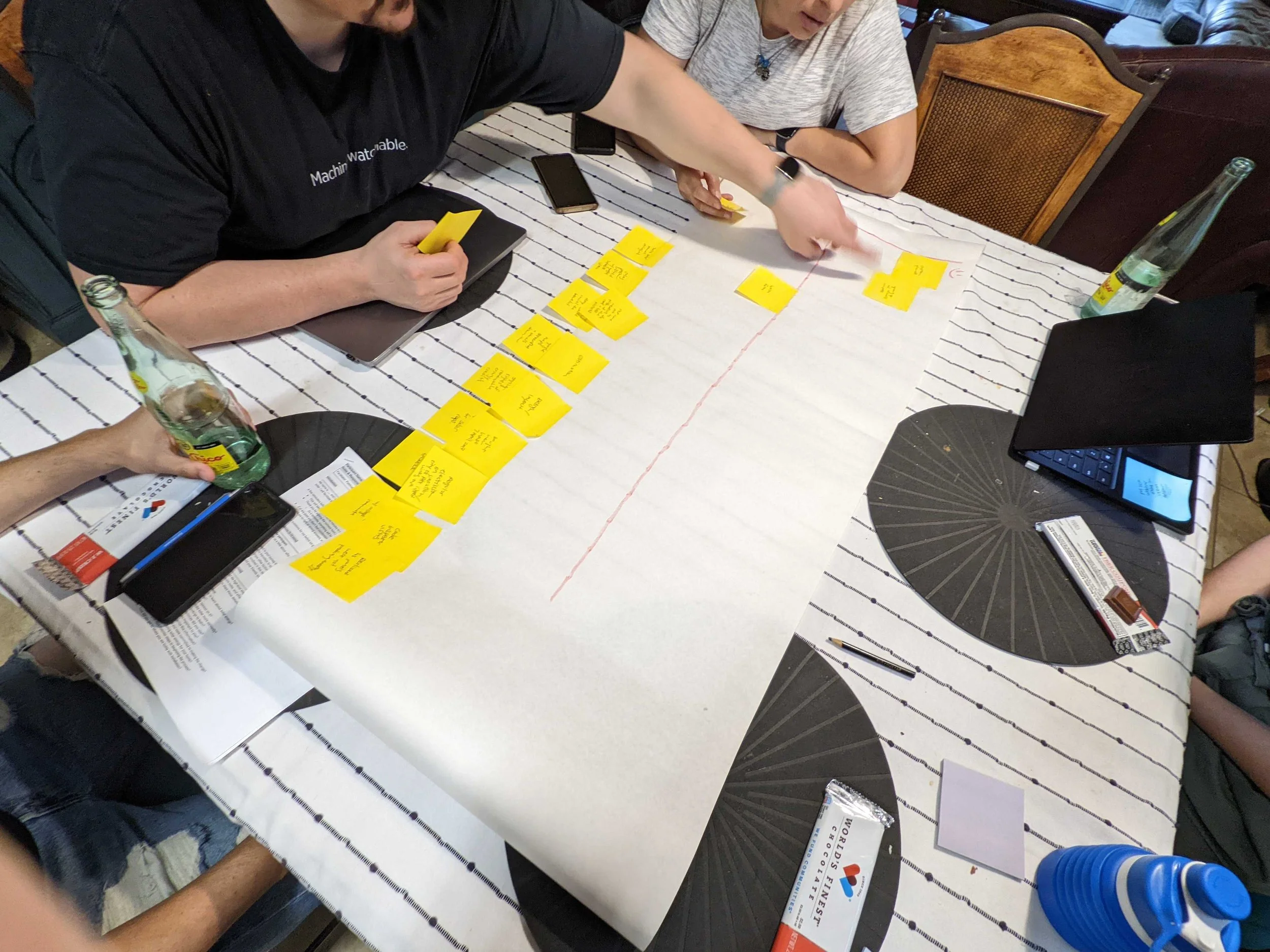

In our teams we worked on the research step first which consisted of coming up with questions and identifying people we wanted to talk to. The topic of research housing affordability. We interviewed people, which was a little scary in the beginning but everyone was very warm and happy to help us out. Everyday was an introduction to a new concept and step in the process and with that new information we’d take our project further. After collecting the data, we learned to sort through it.

The next step - synthesis was a mind melting exercise that I know I need to do a lot more of. The goal of synthesis was to find meaningful information from all that the users had shared with us and then look for themes and patterns across information shared by multiple users. As you start to move data (utterances) around and start to see themes across different users, insights might start to jump out at you or you just stare at your board of post-its until your eyes water and create one out of thin air. It’s ok to be wrong. It’s all iterative.

Now once there are some insights ready as the starting ingredient of the next step - ideation, we get ready to suspend judgment and focus on writing down as many ideas as we can. This was really hard for me, the judgment of what’s a good idea or not, what’s an idea or just some thought floating around in my mind was happening so fast and at such a low level that I just couldn’t suspend it. It was fun but it could’ve been more fun. Sometimes I’m the enemy of fun, another thing to (un)learn while in this program!

There were a couple of interesting moments / experiences that I want to share:

First was realizing that it was hard to put down one of the hats I’d been wearing for many years (software dev). I just wanted to propose interesting and fun software solutions before even studying the problem and the users’ needs properly. It was happening at a very automatic level. So it will take some intentional practice to suspend that part as well.

The second experience was this big dose of expectation adjustment that felt awful and great at the same time. We want to learn about specific users and how we could help them. We want to propose solutions that help in the long-term and address the big picture issues but we also need to understand the scope. The larger issue might be income inequality but that’s not really an insight, that’s known knowledge so when looking for insights there is a sweet spot on that big picture and personal, lived experience spectrum. And it’s hard to find that but that’s a starting point. That insight.

My fellow classmates and the instructors all come from such interesting professional and cultural backgrounds. It’s been one of the most welcoming and kind groups of people that I’ve met. It would make sense that this community attracts highly empathetic people who are all here to create meaningful things. My first 1.5 weeks at AC4D have been energizing and my mind is buzzing with thoughts and the anticipation of shared learning, exploration of ideas, and building of things.

We don’t have the luxury of simplifying the world or starting from scratch. We have to begin from here. In the AC4D program I’m hoping to learn the tools I need, and find the community I need, to not be afraid of that next step.

Now, to quote an Austin mural artist who in turn drew inspiration from MLK Jr’s words, “Where do we grow from here?”

__________________________________________________________________________

[ I’m not sure if the original mural is still there but there are many photographs of it over the years. The artist wanted to bring attention to the displacement of the original residents of East Austin neighborhoods. ]

Fast-paced learning: Orientation Week at AC4D

So Monday (Jan 9) came, there was a lot going on and I was excited. Having recently arrived to Austin all the way from Lima, Peru (all by myself). I had been to the US before, but never to Texas let alone Austin. So everything was a bit overwhelming at start, until Monday came and we had a group lunch in which we got to know each other over great food (loved Tacodeli by the way), after that I felt relieved in the sense that I’ll be spending the next 9 months with great, easy-going people that are super knowledgable and kind to each other.

When the first class started, we went over the Design Thinking process, which was very -as we say in Spanish- “a la vena”, a concise and straight to the point overview of it and then immediately started working on deliverables.

The idea behind the first week of orientation is to go over the whole design process in a 5 day sprint, so students can get a hold on what its like to start from research and end up in a testable deliverable, which I think is great because it actually prepares you for a real world situation in which you have to pivot focus and deliver with a tight time constraint.

By day two we were already talking to people, which can be a bit intimidating at first, but rest assured everyone is very open to help, and if they’re not, just move on to the next one. I know this is easier said than done, but over time you’ll learn to overcome rejection and just focus on the people actually interested in answering your questions.

An advice I can give to people considering the program and woking a full 9 to 5, which is my case, would be to do it! It will for sure broaden your skillset, help you work under pressure, and you get to have fun while at it!

Just make sure to set some time apart, or organize your schedule in a timely manner, that way you can plan your day in ‘chunks’, so you don’t feel overwhelmed (as I did).

I hope my experience can be helpful for your, and if you’re considering to apply feel free to reach out!

Wax On, Wax Off: A Crash Course in Design and Life

Orientation Week has just wrapped up at AC4D, yet the nervous excitement in my stomach is thriving. This feeling is exactly what I’ve been looking for, but I didn’t expect to feel it so quickly. (More on this momentarily.)

Over the course of the past week, we’ve spent each day focusing on a different aspect of the design process:

The AC4D Design Process

As each day unfolded and we sampled just a small, yet dense taste of each step in the process, my mind kept rehearsing the infamous Wax On, Wax Off scene from the The Karate Kid:

Spoiler alert: Mr. Miyagi is secretly teaching Daniel how to fight, but Daniel doesn’t realize it yet.

Day 3 (Synthesis) involved the most mental gymnastics because we spent a majority of our time making the abstract concrete, finding themes in our research and creating insights from those themes. Not by coincidence, it was on this day when I had the aha moment: AC4D is playing the role of Mr. Miyagi, training me how to “fight” without me realizing it.

“Fighting” in this case, though, means developing skills like navigating ambiguity, embracing change, and gaining empathy. Skills one needs not only in design, but in life. Wax on, wax off.

So why have I been looking for the feeling of nervous excitement? Because it’s proof that I’m right where I should be.

My goal in attending this program, among many goals, is to become a great designer. Obviously, that won’t happen overnight. The design process is an iterative, never ending journey. When prototyping and testing are complete, research starts all over again. (See above.)

Life, like the design process, is an iterative journey, and we often learn lessons without even realizing it. What I learned in Orientation Week is to enjoy the journey. Yes, I want to be a great designer, but what I want more is to simply allow AC4D to Miyagi me into becoming a better person through design.

Wax on, wax off.

My Bootcamp in Retrospect

If you’re like many people, while you may have heard the terms “design thinking” or “human-centered design,” you may likely be wondering just what exactly do they mean? I fortunately had the experience of participating in a design thinking bootcamp last week, in which we covered the entire design thinking process — from start to finish.

To begin, like most projects, a designer must embark on the process of conducting research. Although similar to other forms of research in many ways (e.g., interviews, questionnaires, etc.), what distinguishes design research from other forms is that it places a premium on immersing the researcher (or research team) into the actual context of the problem they’re trying to solve, in order to not only gather useful data but also gain empathy with those they are learning about. Transcribing interviews is a beneficial tool for design researchers during this process, as it allows them to later reflect on what participants had to convey.

After they feel they have conducted enough research, the designers go to work on trying to make sense of it. In this process — referred to as “synthesis” — the researchers are attempting to draw inferences. But unlike some other forms of research, the designer must externalize what they have learned by taking the knowledge from their head (or computer or piece of paper, etc.) and putting it in the form of chunks of data that are usable. Doing so allows them to combine participant feedback in various ways, create new insights, and identify underlying patterns or anomalies.

Next, the designer begins to ideate. In this phase of the design thinking process, the designer is suspending their judgement, and simply creating new opportunities that were revealed from user needs uncovered by the previous research and synthesis processes. This type of thinking if often called “divergent thinking,” and is the process of generating lots and lots of ideas while turning off your inner critic.

As opposed to divergent thinking, in the final design thinking phase, “convergent thinking” begins to take place, in which the designer begins to sort ideas that are more plausible from those that seem impossible or unhelpful in solving the design problem they’re working on. In this phase of prototyping and testing, the designer actually begins to bring ideas to life. In an attempt to validate their hypothesis, they make things and build models, which are then used by real people in the real world. As the prototype gains popularity and traction with the people actually using it, the designer begins to shift from lower fidelity models to higher fidelity ones — ultimately, until a final product, service or solution is created.

Note that although the processes are presented in a linear fashion, they are often adaptive in nature (i.e., iterative or incremental, as in agile project management) and non-linear.

Jumping into AC4D.

If you've ever been to Barton Springs, a spring fed pool in Austin, you know that there are only two ways to immerse yourself in the icy water... Slowly wade in, or jump. Orientation at AC4D felt like jumping right in to the icy cold water. Aside from the occasional team-building exercise, we dove into the design process itself, applying it to the complex and multifaceted problem of housing access and affordability.

RESEARCH: We were first paired with a partner in our cohort and assigned to come up with a focus statement for our research. The next step was to design a research plan. We came up with open ended questions and found 7 people to interview about their experience finding housing in past few years. As intimidating as it was to ask people if we could interview them, we did not have trouble finding participants willing to share their stories.

SYNTHESIS: The next step was to synthesize the information we obtained from our interviews. We transcribed the interviews, so that we could find meaningful information easily. We wrote utterances on stickie notes using an online collaboration tool called Mural. Next, we grouped together the utterances based on commonalities, which allowed us to determine themes within our data. Our themes helped us develop insights, to explain our observations. Insights are framed as a statement of truth (that could be wrong) and should be definitive, provocative and complete.

IDEATION: During the last evening class, we spent time ideating. The goal was to come up with as many ideas as possible (quality over quantity) for how we could solve our problem. I initially felt a mental block from a desire to only come up with what I thought were “good ideas,” but I was able to set that aside due to the absurdity of some of the prompts we were given. Letting go of judgement of myself was an important part of the process when ideating. We then learned methods to narrow down our ideas to find the ones that we believed were the best.

PROTOTYPING: Next, we learned different methods for prototyping and created comic-book styled storyboards with an idea formulated during the Ideation phase. These depicted a scenario in which a user experiences our proposed solution. It was fun to see everyones creative approaches and stories.

Upon reflection of this week,

Here is what surprised me:

Asking the right questions is more challenging than I had thought. While I was transcribing the information and noting utterances, I realized that I should have asked follow up questions to learn more about peoples pain points. This would have made it easier for me to find common themes.

Peoples like to share their stories. I initially was intimidated to ask people to interview, but found that people were willing to share their experiences. Having conversations with people outside of my direct community, offered a valuable perspective .

Remote collaboration is not as hard as I thought it would be. I have never been in a professional setting where we communicated remotely. I thought it would be harder to collaborate online, but with my partner being in California, I was surprised to find that we were able to communicate well via Slack, Zoom and Mural.

Here is what I am still curious about:

How do I best organize my work? Due to moving quickly through the process, it was hard for me to stay organized. As a result, sorting through information was challenging. I am looking forward to learning techniques and tools that will help me improve my organization skills.

How will all of our unique perspectives contribute to this experience? With students and professors coming from many different backgrounds and careers, I am looking forward to the ways in which we will learn from each other. I wonder how it will influence where we direct our research.

Parsing through the ambiguity. It is not easy to think about finding solutions to problems as complicated as housing affordability. We are told to roll with the ambiguity, but I am curious to see how the process will help us uncover concrete solutions.

Orientation week at AC4D was challenging and time consuming. I enjoyed the process, but I was definitely overwhelmed at the amount of work I had during the week. I learned a lot of ways to improve the way I approach problems, and I am looking forward to putting them into practice in the coming weeks.

Orientation Reflection

My first week of orientation at AC4D felt a lot like drinking water from a fire hose at first. The orientation is for a UX/UI design certification; UX/UI design is about creating products that meaningfully impact the lives of users, ensuring the design is accessible, enjoyable, and created around the user’s needs. The orientation was a good introductory on some basic tenants for good design, how to identify problems, and how to begin creating solutions to these problems. I was most surprised by how much I needed to adjust my expectations of “success” in a learning environment. In previous schooling there has been a lot of rote memorization, a lot of “this will be on a test later”, and a lot of protocol for each issue. I think I initially approached learning in orientation with the same approach of trying to memorize ideas and concepts and expecting a binary of successful/unsuccessful and right/wrong, which was my experience of learning in the medical field. Once I was able to approach learning and problem solving from the idea of each answer as a step toward a solution rather than the conclusion of a problem, I felt I was able to better engage in lessons. I am still curious about how research questions are established within a company, and what happens the next step is with wire frames. I’m excited for week one of class to officially begin!

Week 4: Notes from the Field

Hello again, AC4D community!

We’re finishing up our second week of interviewing Austin residents about their gardening learning journeys, and we have some themes we’d like to share.

First, here’s a quick glance at where we are in the research timeline:

Next, we’re discovering that a lot of folks have encountered some unexpected surprises along the way, both positive and negative, as they’ve learned how to garden.

While people have shared with us the different learning approaches they’ve taken (from self-taught, to signing up for gardening-focused events and programs), what we’ve found to be illuminating in their stories are the lessons they’ve taken away from their gardening experiences.

Here are some high-level findings accompanied by snapshots and quotes that capture what we’re hearing in our interviews:

1. People gain deeper insight into their personal values when learning how to garden.

Participants are sharing what they’ve learned themselves in the process of learning how to garden, and how these takeaways have either reinforced or shifted their perspective on how they approach other parts of their lives.

“When I was growing up, it was definitely like, I'm not ready yet. I have to be 100% and have to be perfect before I can apply for this, or before I can do this… that kind of mindset is changing more and more.”

– Leah

“I've learned a lot of humbleness and grace. […] Connecting back to [this knowledge as an Indigenous person] feels like work that is multi-layered and multi-dimensional… this is mind, body, spirit. This has the power to heal in all the ways, generationally. It's felt really powerful taking back personal autonomy and control of my own wellness and destiny.” – Jay

2. It’s difficult for gardeners to find the right resources at the right time.

While people are eager to learn more about gardening, oftentimes the challenge is finding the right information when they need it. Gardeners described a common issue of not knowing where or how to start looking for resources.

“I had no idea how many free resources were even available to the community until I was working in that [garden science program].”

– Cara

“There's a lack of education and clear information that is just out in the public… it's not out there, readily accessible. […] [People] don't know where to find the information and they're just like, I don't have a green thumb because all my plants are dying. But what might be the thing, is that they're not working with reasonable plants that are heat resistant. They don't know about the use of compost and mulch, they don't know about all these other factors.” – Jay

3. While gardening fosters community in many ways, it can also stir up tension.

Building community and finding a sense of community through gardening are both things we’ve heard. Yet, something we’ve also come across in our research is that there are gardeners who can behave in ways that are not always community-focused or -driven.

For instance, a SME we spoke with early on, who serves on the board of a community garden, mentioned that members don’t always get along, and sometimes conflicts arise, for numerous reasons. This can range from veggie theft to other petty conflicts. There are even conflict resolution workshops offered for people who are part of community gardens.

Here, Cara shares the juxtaposition of the joy she finds in knowledge-sharing and seed-sharing with fellow gardeners, and then trying to bring attention to a potential gardening issue with other members of a Facebook group, only to be met with hostility:

“Community is one of the biggest things. I've started sharing seeds and trading seeds with people… when I'm able to gift somebody a plant that I grew, or even some seeds that I collected, that's one of the best parts of connection and a community. [But] I posted in [a gardening Facebook group] yesterday, and it was this whole drama. I was just trying to figure out if other people were having the same experience [...] but there were people who were just kind of mean about it [...] like, this is the best way to do it.” – Cara

In another example, Cara shared about other people encroaching on her beds, despite explicitly asking them not to do so:

“We sometimes had issues with the staff… ask them to not touch our garden beds, but they would still spray them [with pesticides or herbicides] because people have their ideas of what they think is best. It's hard to persuade them otherwise, sometimes. […] I feel like it's like raising children… like you're telling somebody how to discipline their child or something, and people get very offended, sensitive about it.” – Cara

4. Gardeners don’t just want their plants to survive – they want them to thrive.

People have described developing a personal connection to their plants and feeling responsible for keeping them strong and healthy.

In one of our favorite anecdotes to date, Sally, a patio gardener in east Austin, describes high-fiving her plants when they’re doing well:

“Sometimes I'll be really upset or have a hard time at work. And these plants are still thriving. I’m giving little high-fives [to them]... ‘Cause they're trying their best, and I'm trying my best, and I'm like, you're doing a good job, buddy.” – Sally

Another gardener, Cara, shared with us that she still drives by the garden she tended to at her last residence to see how her plants are doing:

“I wish I could see them come to fruition. I still drive by [my previous garden] sometimes.” – Cara

Next Steps

This upcoming week, we’re continuing our research by interviewing three gardeners we’ve lined up as well as speaking to two additional SMEs who are part of organizations that offer gardening learning opportunities. We’ll also conduct intercepts at two community gardens in Austin.

We look forward to sharing more with you in the coming weeks!

Arielle Schoen + Annie Ly

Learning English Unlocks Doors

“It was the key because you know, if I was not able to learn English and communicate, I was not able to do all the things that I feel that I’ve been accomplish and doing all this time.”

This week, we (Jo, Linnea, and I) conducted interviews with 10 women who have walked the journey of learning English as a Second Language (ESL) since moving to the U.S. Through our initial outreach to 20 local organizations working to support immigrants and refugees in various ways, including language learning, we built trust and connections that led these women to step forward as volunteers to share their stories with us. When we asked them why they volunteered, many of them told us that they wanted their stories to be heard - and wanted to take advantage of any opportunity to practice!

Timeline — where we are now

Themes

Below are three high-level themes that we have identified across ten interviews. We gathered this data through in-depth interview questions and a participatory exercise using visual stimuli. Please note that there are grammatical errors in the quotations below. We intentionally used the participants’ English words verbatim to honor their learning experiences.

1. The process of intentionally writing down unknown words supports learning.

“But sometimes I don't know this word, I write it in my paper. [...] After that I look in the dictionary, this word. [...] Sometimes, I don't know how to pronounce how to the meaning. I write it on here. [...] In my pronunciation class I asked my teacher.” — Amira

Mitra’s notebook where she writes and learns new words.

“I wrote down all of new word on my notebook. Write it down one side English other side is Dari. I practice when I wash the dishes. Just I look at it when I forgot, for example, after two days when I need that word [...] I grabbed my other notebook. I looked the word. For example like this, when you are "frugal", it's new word for me.” — Mitra

Irena has a list full of words in her notebook. On one page, she wrote:

Other = a different one

Another = more of the same

2. Having a safe space to practice English is critical to move forward in learning.

“For me it [classes at ACC] was very hard. I don't feel comfortable when I was talking with a teacher in front because I feel shy because maybe I don't know speaking very well. So maybe somebody is better than me. ” — Victoria

“I think when you have these community programs, that really helps the community because then you feel like you're part of the community. And they’re doing that for you because they care for you.” — Isabel

“When I read that essay I was stuck. I was stuck on that. All of my classmates laugh at me. Ashamed, I was ashamed.I was scared or afraid. One day I said, ‘I don't want to go to the class anymore.’— Mitra

3. Having an English-speaking community or network is critical to learning.

“Because we live among more people who speak more Spanish I think we forget how to speak English. [...] You don't need any more English, because everything is in Spanish or they talk to you in Spanish.” — Elena

“In my job, in my language, in my relationship with the other persons. Here in Austin the most people in the places speak in Spanish. So for me it's easy, but no is good.” — Victoria

A positive learning experience from Marisol about having friends who speak English.

“We moved to art and craft shows and all these art and craft shows primarily had more Anglo people. They speak English and I still have a lot of friends that speak English. [...] I will say three or four years after doing that, I feel like little by little I start understanding what they were saying to me and feeling comfortable to answer back.” — Tessa

“It was mainly Spanish, but then I kind of was forced to learn it because I have to work with the church staff and some of them speak English and Spanish [...] that’s when I feel that I need to learn the language. Because I feel like it was good that I was helping in Spanish, but at the same time, I feel like if I'm gonna be a bridge or a connection between the English speakers and the Spanish speakers, I need to be in the middle, right? So I learned.” — Isabel

Next Steps

Conduct one interview on Friday, April 15 and one interview on Tuesday, April 19

Continue synthesizing the research data to develop themes and insights

We plan to observe and participate in Conversation Class through Ladies Let’s Talk on Friday, April 22

Solar Research Check-In Week 4

We are in our fourth week of our capstone project. This blog post is an update on where we are, insights we have found, and where we are going next.

Focus Statement

What have Central Texas homeowners learned in the process of transitioning to solar energy, and what were the gaps in their expectations versus the realities of their lived experience?

Initial Findings

Below are some initial findings from our interviews with the following three participants/households:

Scott, a retired man from Wimberly who installed solar panels on his home very recently.

Peter and Nancy, a couple with one son who installed solar on their home after their experience living through the 2021 winter storm.

Pedro and Lily, a couple with three daughters who installed solar on their home after a salesperson came to their house.

1. Information about climate change is learned passively throughout their lifetime.

The participants that we have interviewed struggle to think of the specific times they first encountered and learned about the problem of climate change. But when they dig deep, they recall the points in time at which they saw a show, read a newspaper article, or had a conversation with a friend that framed their understanding of climate change. These points in time occur all throughout their lives, passively informing their opinions and the choices they make.

For example, Pedro tried to recall what influenced his early perspectives on climate change, and struggled to come up with one defining moment.

“I mean, I grew up with Captain Planet and stuff [...] I remember one conversation I was having with my roommate. In college, we were talking about climate change. [...] but I can't think of when I was convinced that climate change is bad?” - Pedro

In contrast, Nina had some experience learning about climate change from her job,

“[As a marketing researcher] I get to listen to podcasts about solar. Amazing! I think [installing residential solar] was one of the key things that instantly made sense to me because I had that background.” - Nina

When asked if there was a specific climate event is evident in his mind.

“Oh, no, this has been gradual [...] It's just been on my mind forever.” - Scott

2. A catalyst event can trigger someone who is passively learning about solar energy into being actively committed to installing solar panels on their home.

Peter and Nina experienced living through the winter storm of 2021 for four days without electricity. In our conversation with them, Nina recounted staying at their friend’s house in close quarters:

“It was the two of us with our son, and our two dogs, in a two bedroom apartment, with a man who has his own cat. And it was a lot! I'm glad we're still friends.” - Nina

Overall, they were primarily concerned for their young son, who was frightened due to the uncertainty of the situation.

While they were in their friend’s living room, they googled solar companies and started making calls, knowing it could provide them a backup system should their house ever lose electricity from the grid again. Their desire to avoid another power-less situation led them to committing to and installing solar less than a year later.

“I think our bottom line was, we never want what happened last February to happen again." - Nina

Recruiting & Next Steps

We plan to interview 12 participants by April 22. We have used a variety of recruiting methods such as:

Emailing solar businesses for referrals.

Posting on online forums.

Leaving flyers at houses with solar panels.

To date, we have:

Completed 4 interviews.

Scheduled 5 interviews.

Engaged with 3 other participants who are in the process of booking an interview.

Met with a Subject Matter expert.

Our next steps will be to continue recruiting participants, and secure interviews with the 5 participants pending booking. As we gather data from our interviews, we will continue to expand and develop our growing list of themes.

Work produced by Olivia Posner, Jacob Pfeifer, & Patricia Nuñez

Notes from the Field: Learning How to Garden

Hi, AC4D community!

We’ve had a fruitful (get it?) week of kicking off our research on how people who don’t own land or property learn how to garden.

Here’s what we’ve done so far:

Direct observations of two instructor-led group classes:

Here’s a view from when we directly observed an instructor-led class last week. To learn specific gardening skills, people sign up for hands-on experiences to fast-track

their learning. This particular workshop was focused on the basics of companion planting.

…one interview with an instructor who still considers himself to be a student:

Jay (far right), who learned

how to garden during the pandemic, has now become

a gardening and herbalism instructor to both children

and adults.

Jay attended the same companion planting workshop we did and soon started thinking of ways to introduce companion planting to his younger students this week.

…and one phone conversation with an SME who is a community garden board member.

Although we’re still in the early stages of our research, we’d like to share our findings with you. Here are some themes that have emerged so far:

Learning how to garden…

teaches humility and grace; nature cannot be controlled, but it can be nurtured

helps people learn how to embrace a growth mindset because it requires time, patience, bouncing back from failures and frustrations, and the ability to flex and adapt to meet the needs of changing conditions and environments

Here’s a quick glance at the rapid synthesis that led to some initial themes.

We’re excited to continue our research with three participants we’ve lined up for the next three days. Here’s who we’re talking to next:

Someone who’s learning how to garden on land shared among members of an intentional community

Someone who’s learning how to garden on their apartment patio

Someone who has learned how to garden in a number of different places across the country, all on land that wasn’t his own

We’re continuing to recruit and will be reaching out directly to five potential participants and SMEs tomorrow to schedule time with them next week for contextual inquiries and in-depth interviews. These people were all leads from folks we’ve already connected with this week, so we’re feeling hopeful and optimistic about our chances of meeting with them.

In addition, we will be doing intercepts at community gardens and casting a wider net via online forums.

We look forward to learning and sharing more in this upcoming week!

Arielle Schoen + Annie Ly

Solar Research Check-In Week 3

Focus Statement

What have Central Texas homeowners learned in the process of transitioning to solar energy, and what were the gaps in their expectations versus the realities of their lived experience?

Initial Findings

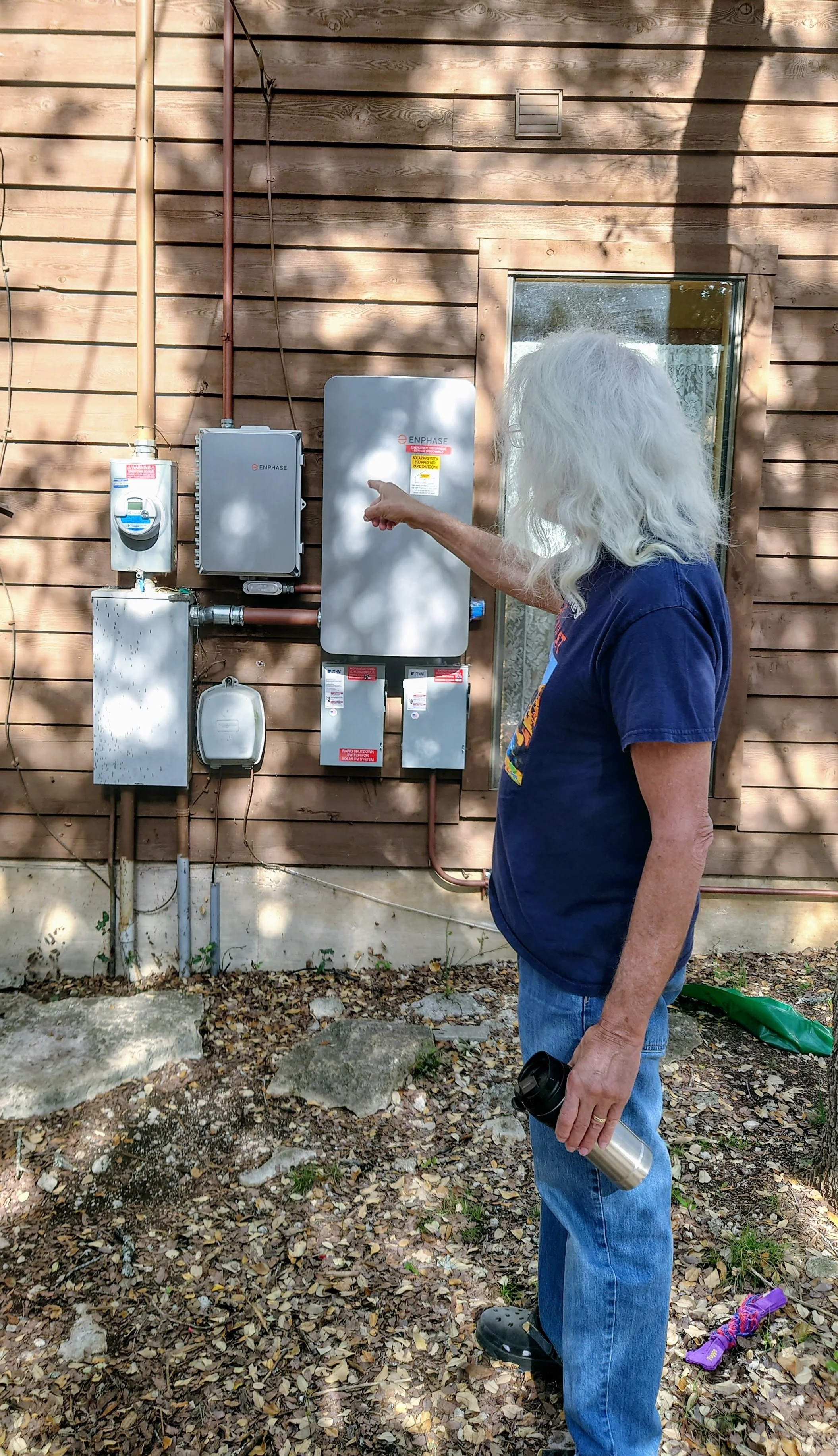

Below are some initial findings from our first interview with Scott, a retired man from Wimberly who installed solar panels on his home very recently.

1. Trust is valuable when buying into solar power.

When Scott was looking into the logistics of installing solar panels on his house, he reached out to several contractors. From then on, he started receiving a large number of emails from salespeople. Scott didn't like that the conversations were more about financing than solar. Scott eventually found a contractor that he liked, and to his surprise, the contractor said that Scott's home was not fit for solar energy. After that, Scott put off solar for five years - convinced it wouldn’t work for his home.

One day, he went to visit a friend, who had installed solar on her home, which convinced him again that it could work for him. Because he received a recommendation from a friend - he was all in, and decided to re-start his solar journey. The company she recommended almost received the status of extended friend - he trusted them completely and did not do any additional research as they were guiding him through the process.

“It is very hard to trust these people that are advertising. […] You can’t hardly trust anything that comes across your phone [...] so actual human conversation is much nicer.”

2. Seeing the visual representation of energy use made him more aware of his impact.

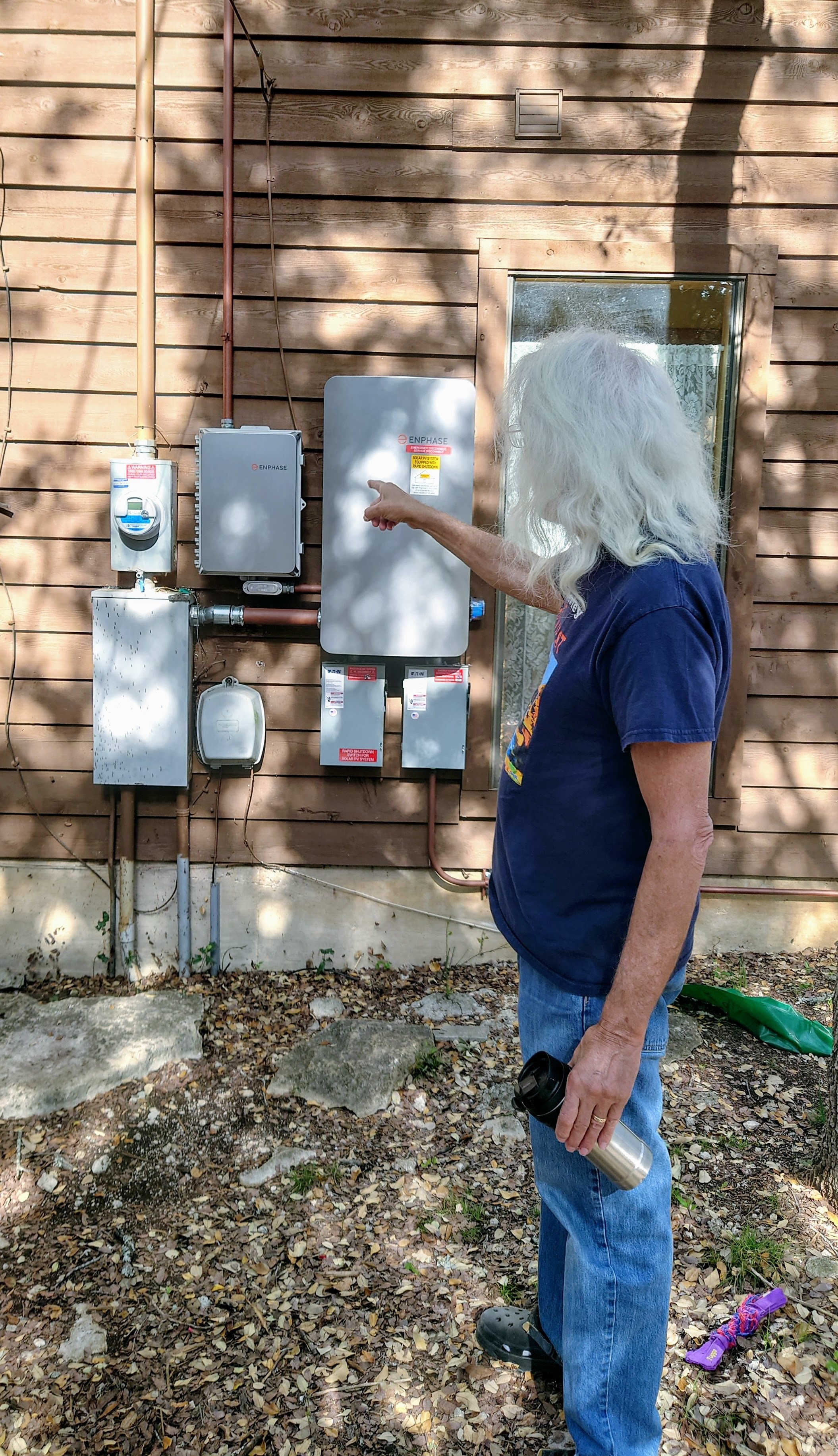

Scott is OBSESSED with his solar tracking app, Enphase. As a retired man, he has a lot of free time, and looks at the app all throughout the day. Because he is constantly checking the app to learn about how his home produces energy, he has gamified his home’s efficiency. One time, he became bewildered when he realized how much energy his dryer uses.

Overall, the app has really expanded his understanding of energy use; and being able to see that information visually has put everything into perspective. While it is not the reason why he became invested in solar, the app has become a useful side effect of the installation.

“So notice that right now we're producing 2.2 kilowatts. We're consuming only .6. We love that. That’s very little…I've never I've never gotten it down to zero. What the hell is it looking for?”

Recruiting & Next Steps

We plan to interview 12 participants by April 22. We have used a variety of recruiting methods such as:

Emailing solar businesses for referrals.

Posting on online forums.

Leaving flyers at houses with solar panels.

To date, we have:

Completed 1 interview.

Scheduled 2 interviews.

Engaged with 5 other participants who are in the process of booking an interview.

Our next steps will be to continue recruiting participants, and secure interviews with the 5 participants pending booking. As we gather data from our interviews, we will continue to expand and develop our growing list of themes.

Work produced by Olivia Posner, Jacob Pfeifer, & Patricia Nuñez

Women Learning English as a Second Language: Research Field Notes

This week we (Jo Arp, Jenny Wong, Linnea Fox) focused on outreach to recruit participants. We contacted over 20 local organizations that teach English as a Second Language (ESL) or support immigrants, refugees, and cultural communities.

Through these recruiting efforts we:

Scheduled 4 interviews

Are in the process of scheduling 6 interviews

Themes

We spoke to two subject matter experts (denoted below as MA and MK) who have dedicated their careers to working with women learning English. We learned:

Community makes a big difference in a woman’s success in learning English

“They could come together, talk to each other after classes, and support each other in that way [...] they interacted like friends, and laughed together” –MA

“One of them was always correcting the others. We felt like if they were comfortable with that, it was better than us being the ones correcting them.” –MA

Language builds confidence and confidence builds power

MK shared a story with us about a young Korean woman whose husband was away at a conference. She was upset because she needed to get money from the bank but did not know how. MK worked with her to fill out sample forms to build her confidence. She was able to successfully take money out and when her husband returned, she had the confidence to do more things herself.

Research Adjustments

Participatory Activity

Subject Matter Expert MK recommended that we use drawing as a form of communication.

We adjusted our participatory activity to have participants draw what they are feeling instead of selecting from a book of visual stimuli.

We will have the book of visual stimuli on hand if the participant is not comfortable with drawing.

In order to put the participants at ease, Subject Matter Expert MA validated that, “It can be helpful to have something else that you are both looking at.”

Introductory Question

We added a question at the beginning of the interview to have participants teach us some words in their language, and allow us to repeat it back to them. Reflecting back on her experience as a teacher, MA said, “It was good for them to see the teachers not know something.”

Next Steps

Conduct the 4 scheduled interviews

Schedule the 6 participants who have verbally agreed to participate

Continue recruiting efforts

Dear Designer

A collaborative poem from the class of 2022 to round out our Q1 theory course in “Public Sector, Innovation, & Impact”, from us to you…

A collaborative poem from the Class of 2022 to round out our Q1 theory course in “Public Sector, Innovation, & Impact”, from us to you:

Dear Designer,

1

Design is scary

Because it can change the world

In ways you don’t know.

Design is power

Giving power to others

Creates more power

Design is caring

Caring is sharing the wealth

The wealth of enough

Tell me a story

Of positive deviance, and

Listen with intent.

we design the world

like a snake eating its tail

it designs us back

Design is justice

And the Designer is grace.

Design is us

Designing for all

Is not unattainable

It just takes our hearts

Listening to you

Will show me what we can do

And we will do it

2

With climate change and the threat of nuclear war, is it about to strike midnight?

It’s time to reimagine how we’re caring for our communities, future generations, and our planet.

Time is a human construct. The world has no time.

The night is tiring, but I must keep working so that I can feel worthy when morning comes.

Time to turn toward community interdependence

Time to tear down the system and try again.

Time to stop sleeping through our alarms.

3

I hear the bees buzz

Trees an endless horizon

The rain smells like life

Morning dew before everyone wakes up at the campground.

Laughter in the forest

…losing your sense of smell due to covid.

A place of belonging, A seat at the table.

My mom’s homemade dumplings.

Hugging friends.

Playing games.

Sleep.

Drinks around a campfire with friends

WOW everyone is so positive

Tasting fresh veggies from the garden (when I finally have time to plant things during our break)

4

Trees are marvelous and offer us clean air to breathe.

“Grace is the breath that we take on our journey, so we don’t pass the fuck out.” (Justin Boyce)

Why are we here now?

Let’s keep our vision steady

Bloom from inside out

It’ll be okay, even if you don’t think it will be.

Just think to yourself, will this matter in 10 years?

If the answer is no, then don’t sweat it.

You did the work to tell this story.

Remember to tell your people that you love them.

Remember that “it’s just a ride”.

[How can we] be here now?

Zine:

My zine focuses on peoples’ complicated relationship with technology. My goal with this zine was to make it personal and to showcase my own struggles with trying to feel present in the midst of a technology-driven world. I included stories of pivotal moments in my life such as when I was a pre-teen and became completely absorbed in my AOL Instant Messenger, Xanga, or Myspace persona rather than hanging out with people IRL, or when I was 19 and spent a month at an intentional community and was able to disconnect from our modern world, connecting instead with myself and those around me. The latter experience had a large impact on how I see the world and prioritize aspects of my life, so I wanted to pay homage to that by modeling this zine after Ram Dass’s book, “Be Here Now,” which he wrote at the same intentional community that I stayed at.

I had a lot of fun with this project and wanted to experiment with collage while also keeping in mind Be Here Now’s typography, imagery, and overall message. I looked through various magazines that my friends and family had on hand (such as National Geographic magazines from Bolivia) and scoured the internet for a font that resembled the book’s font. Take a look at my process and inspiration below!

Process and Inspiration:

I hope you leave this zine/blog post feeling inspired and driven to be here now.